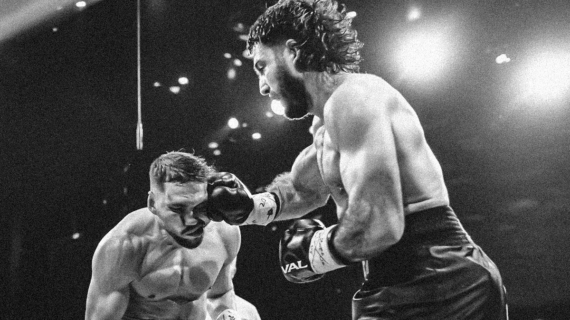

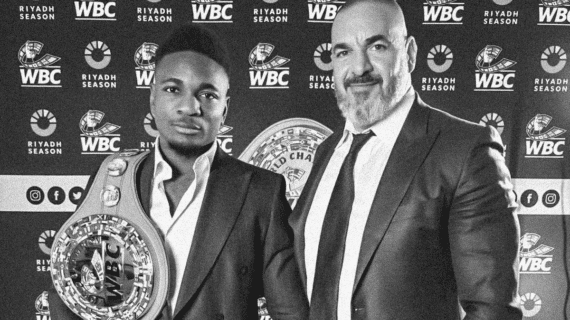

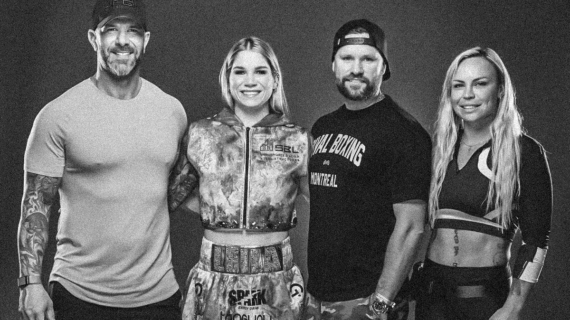

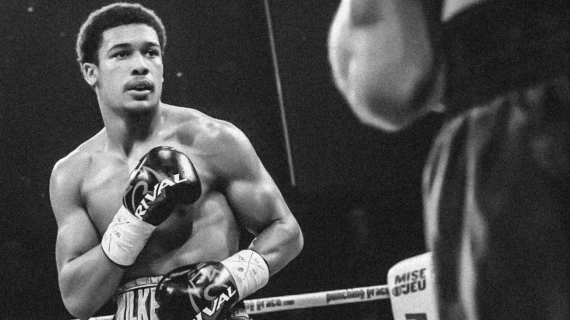

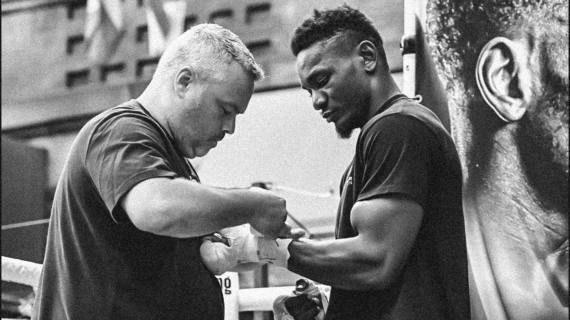

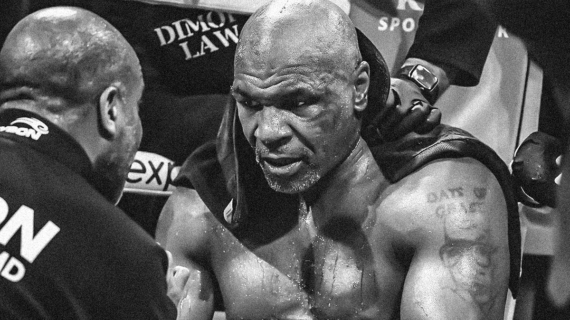

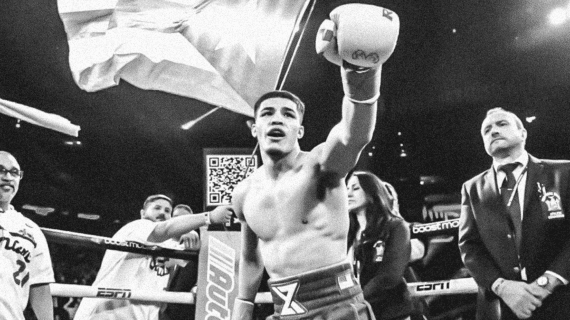

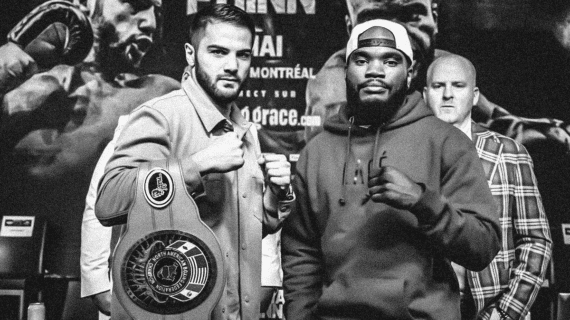

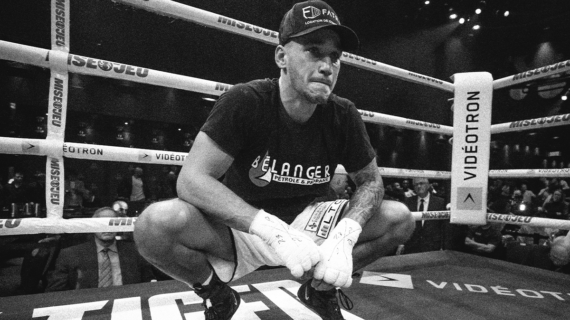

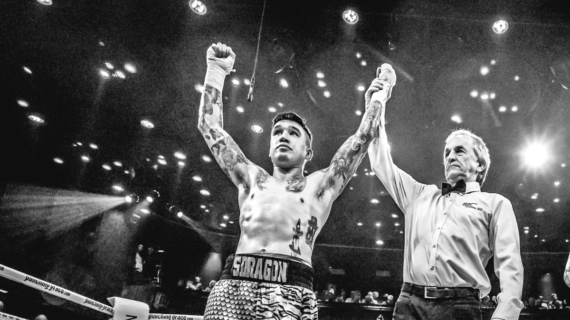

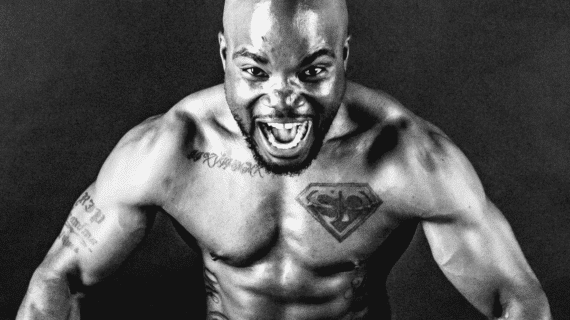

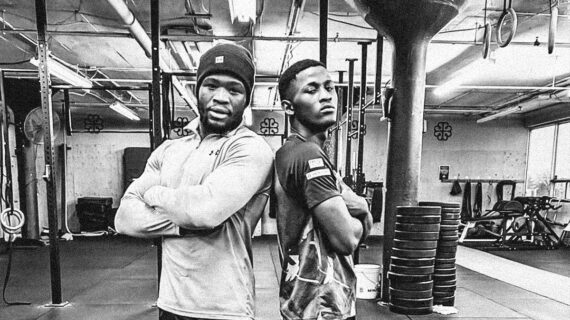

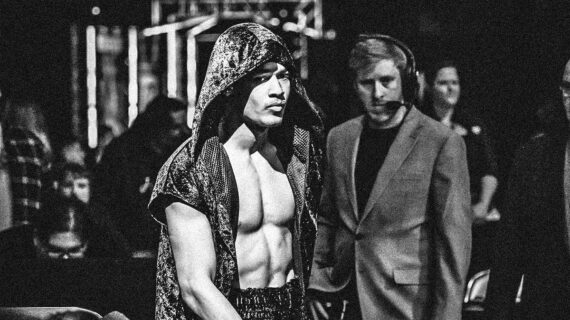

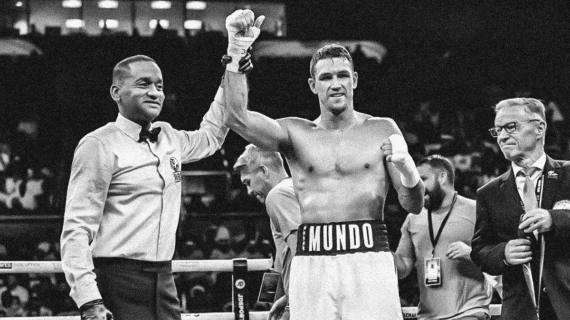

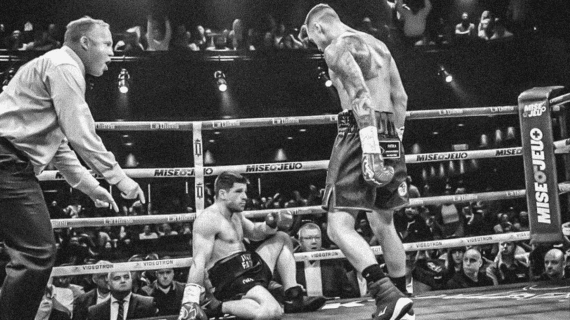

Photo: Vincent Ethier – In the second part of its Cornerman series, Punching Grace sits down with the legendary Mike Moffa, current trainer of Steve Claggett (38-7-2, 26 KOs), Wilkens Mathieu (7-0, 4 KOs), and numerous amateur athletes.

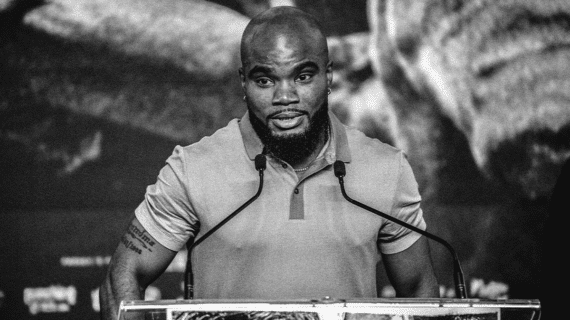

From Montreal to the far reaches of the boxing world, Mike Moffa is one of the most respected coaches. His method has proven itself, both at the amateur and professional levels, where he accepts no half-measures.

“For me, it’s my way, or the door,” he once told Punching Grace, while pointing directly at the door of the Underdog Annex.

But what exactly is the Mike Moffa way?

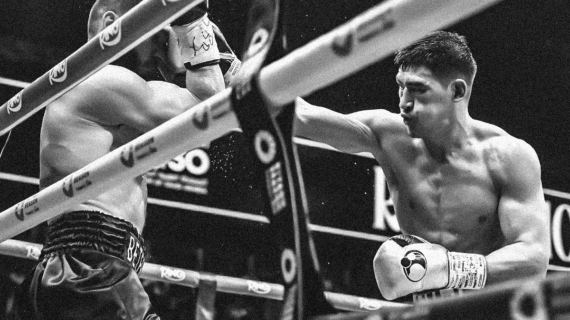

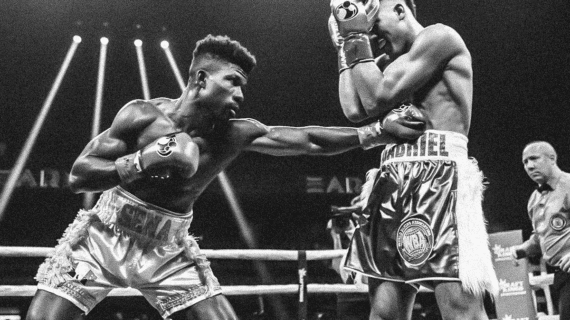

“It’s flat boxing,” he says with a laugh. “It’s being able to win rounds just with your jab. It’s defense before offense, footwork, or just preparing your defensive move as soon as the offensive move is made,” he enumerates.

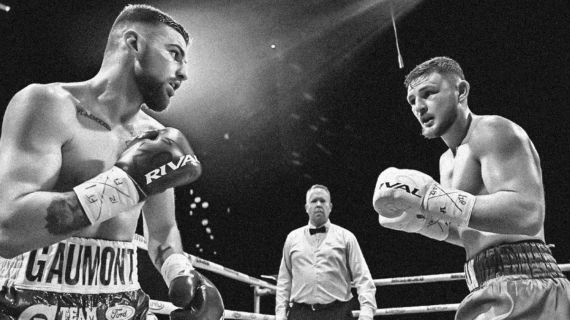

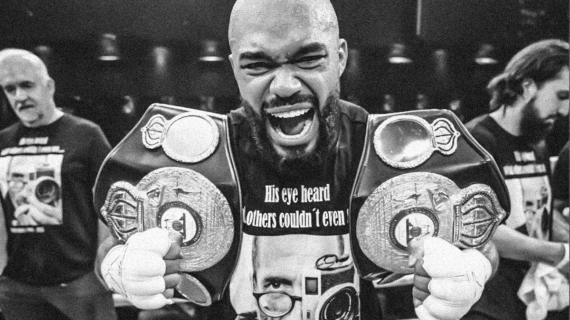

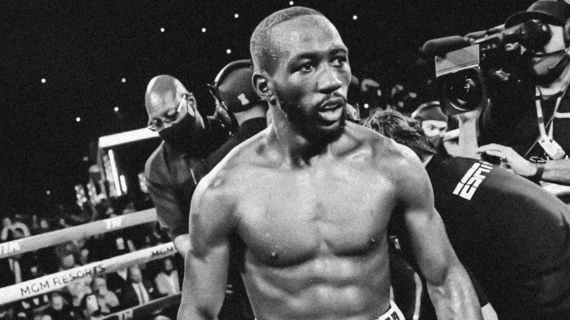

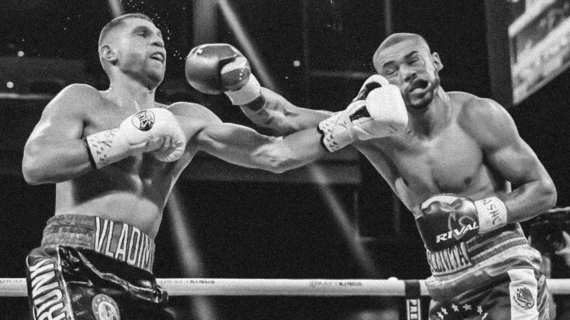

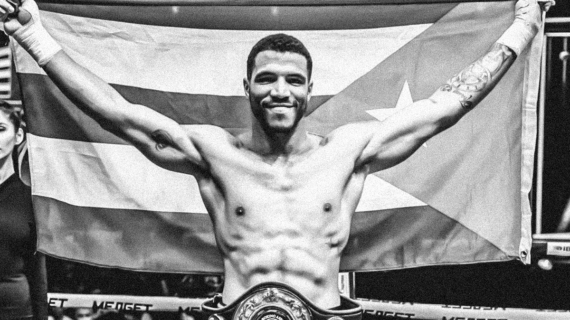

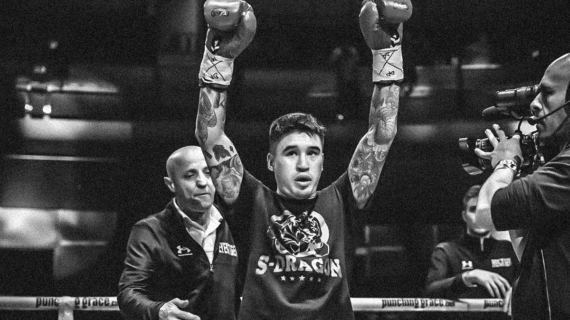

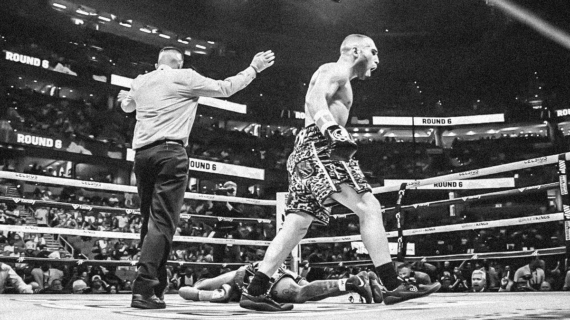

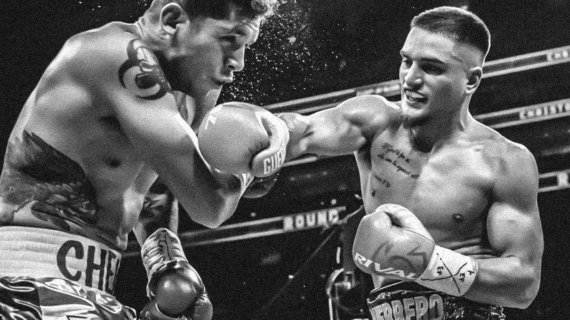

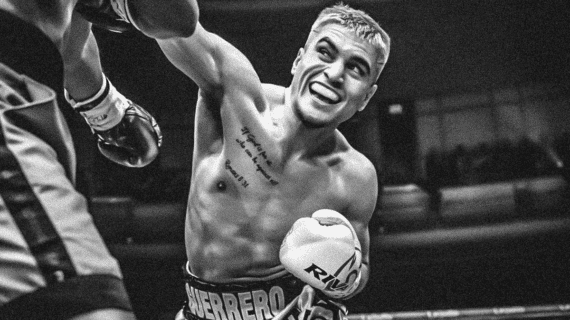

By adding hard work, repetition, and a variety of details tailored to each athlete, it results in fights that are far from “flat.” Just ask Steve Claggett. The Dragon is always spectacular, but now much more incisive: perfect in nine fights since teaming up with the Montrealer.

At the Plaza by himself

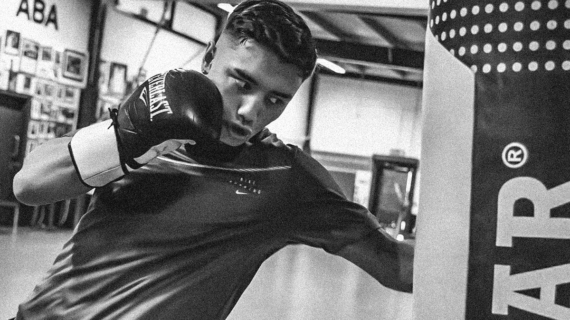

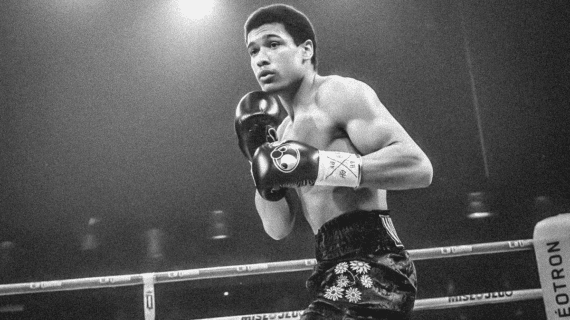

It’s not a recent development that Mike Moffa is the king and master of his affairs. Passionate about sports since childhood, he adopted baseball, hockey, and eventually boxing in the late 1970s. Passionate, but also determined, because everything was at his own expense.

“My father didn’t want anything to do with sports or boxing. At 10 years old, I paid out of my own pocket to take the bus and go to the gym,” he recalls, remembering even more the one time his father came to see him box at the Claude Robillard Center, in a tournament pitting the Canadian national team against Italy’s.

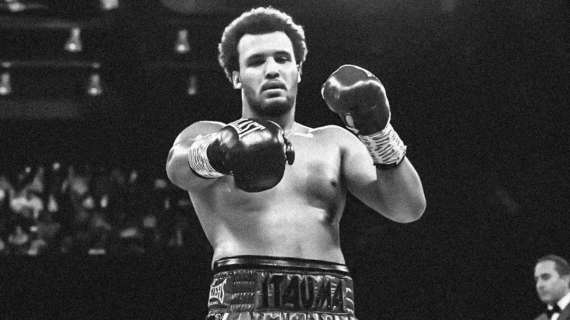

Counting on the support of his coach Dave Campanile at the Plaza Olympic gym on Plaza St-Hubert, Moffa quickly made his bus tickets profitable. In the 1980s, he was crowned Canadian champion four times. With this momentum, he entered the professional ranks in the spring of ’89.

Boxing, party, and coaching

However, the professional adventure was short-lived. After winning his first victory against American Lloyd Ratalsky, he lost in the second round against Dominican Jose Arias. Although he returned to the path of victory in February ’90 in a local fight against Hughes Daigneault, his heart wasn’t in it anymore. With a record of 2-1 in three fights, all fought at the Paul-Sauvé Arena, he hung up his gloves.

“In the end, I saw everything I had missed [in my adolescence]. I loved partying, having fun with girls, clubs, friends… and everything that comes with it. It was the sacrifice I couldn’t make to have a boxing career, because at 21-22-23 years old, I wanted to live it when I was at my peak.”

As we know today, however, boxing was far from being out of his life.

“My coach was like a father, a mother, and a friend to me. He allowed me to stay to help him at the gym. As a coach, the effort isn’t the same, I didn’t have to follow a diet so I could go out, drink, and coach the next day,” he recalls, as this father-son relationship with Campanile was certainly mutual.

“When he died, he left me his gym and that’s when I started taking it more seriously.”

“The boxer makes the coach”

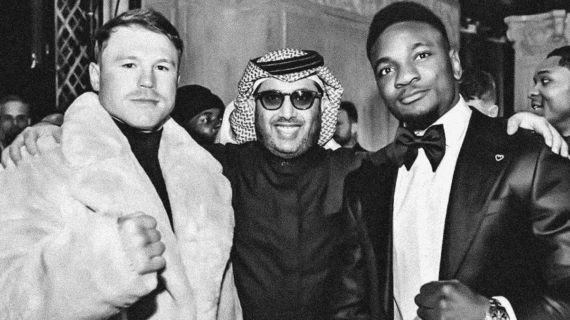

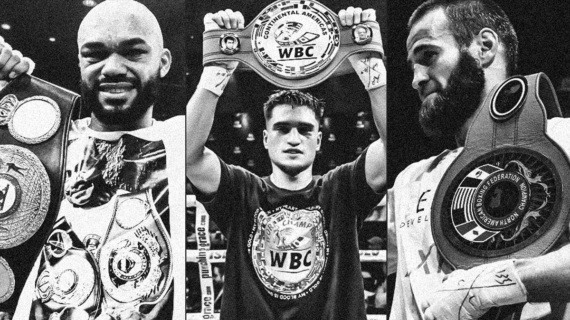

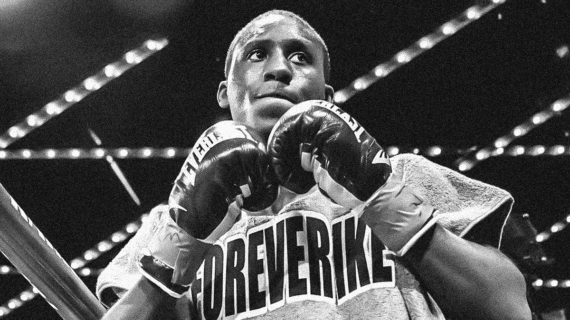

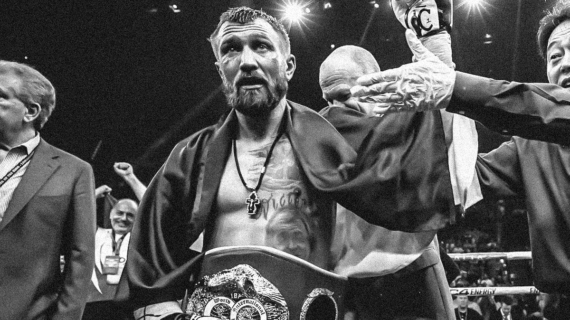

Over the years, the cream of Quebec boxing passed through this gym: Alcine, Pascal, Stevenson, Stiverne… At the dawn of the 2000s, once the glorious days of the Plaza were over, he went through the Legend club and then to Underdog.

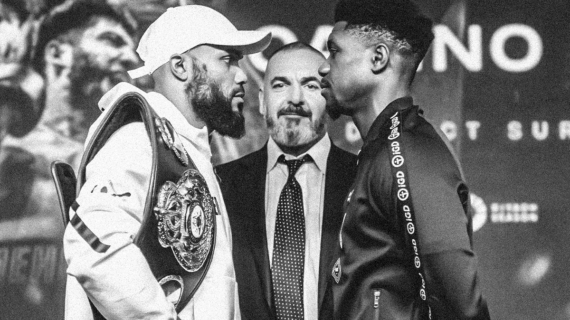

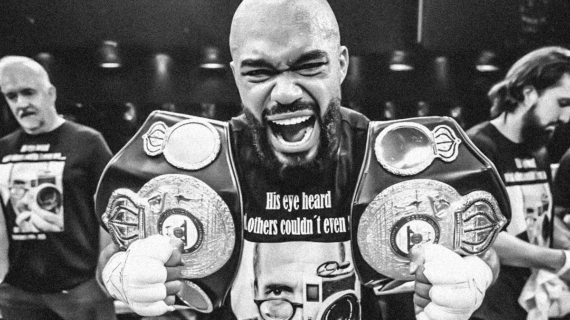

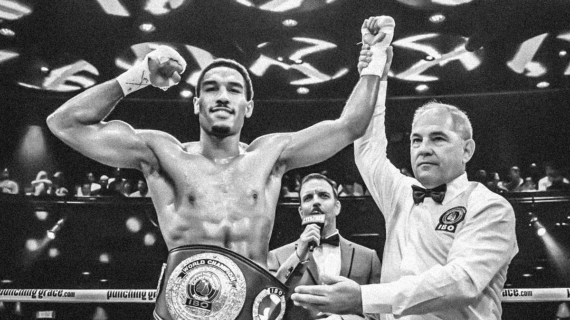

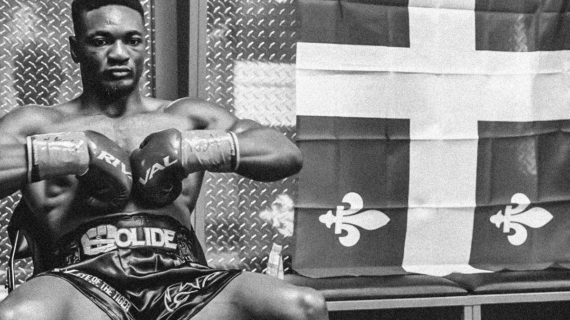

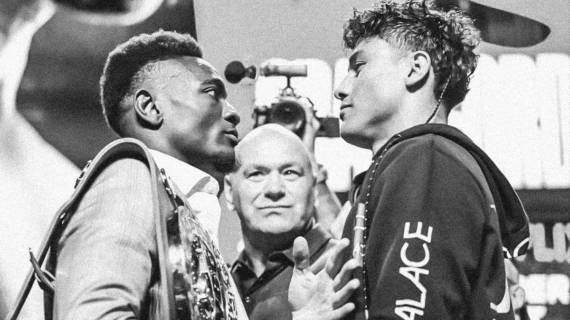

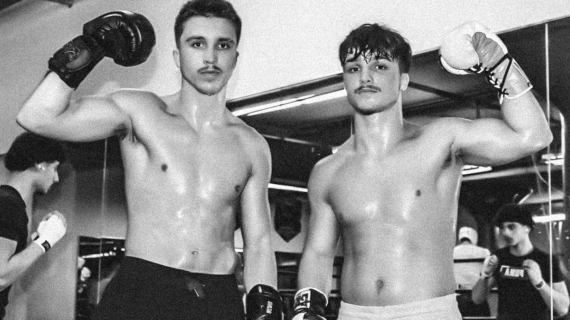

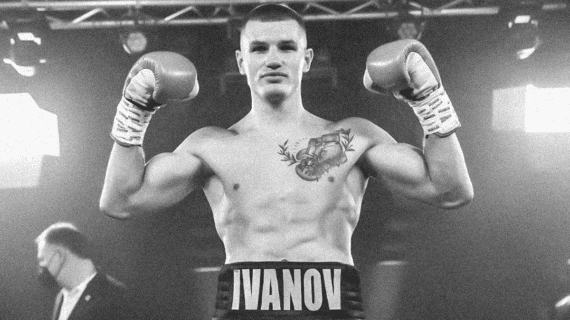

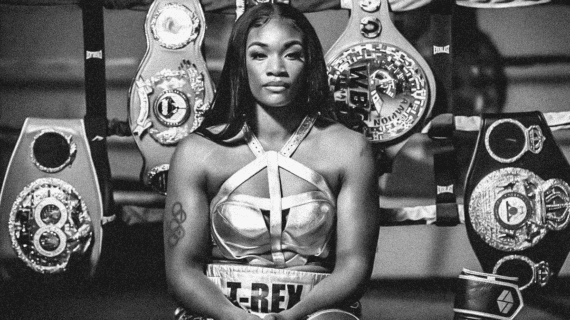

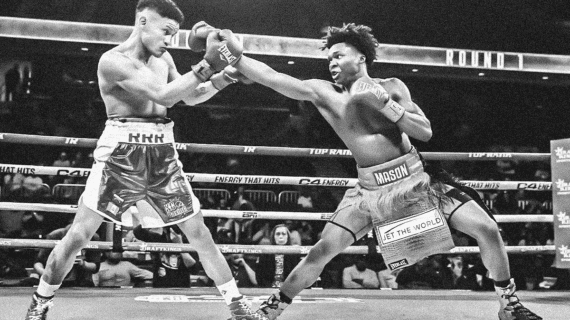

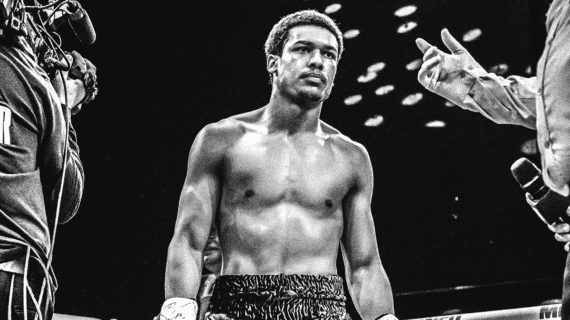

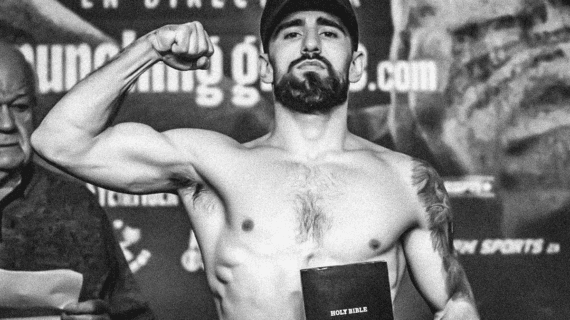

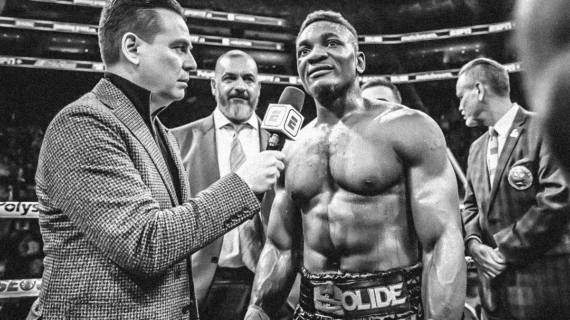

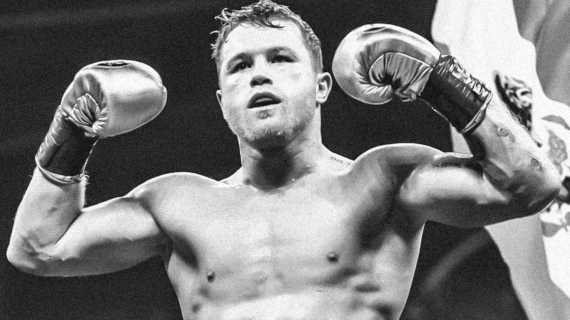

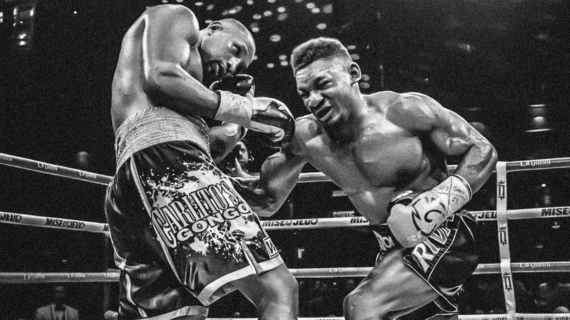

Once there, he was seen alongside Dierry Jean, Ghislain Maduma, Mathieu Germain, and more recently, with Steve Claggett and Wilkens Mathieu. The latter, with his unique talent and contagious determination, even reignited his passion for boxing after he experienced some darker days during the pandemic.

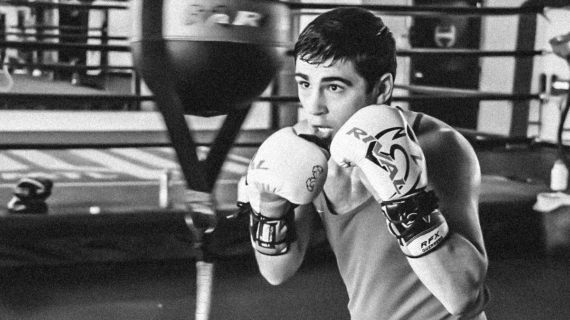

“For me, the boxer makes the coach. The efforts they put in make mine meaningful,” he asserts, taking the example of Wilkens Mathieu again.

“He has talent, skills, he hits and he works! At the top, they all have talent, so if he doesn’t become world champion, it’s because he stopped putting in the effort.”

We’ll revisit this text in a few years, allowing ourselves the right to dream in the meantime.

The greatest hits

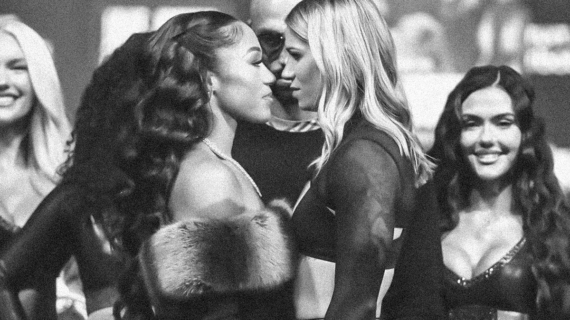

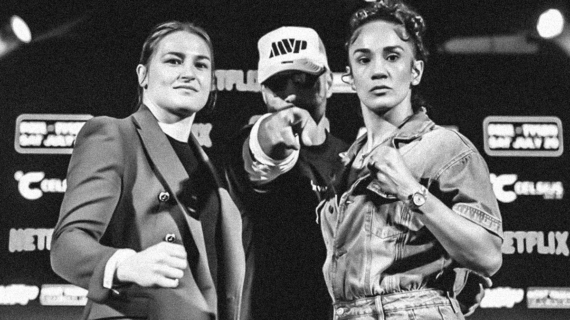

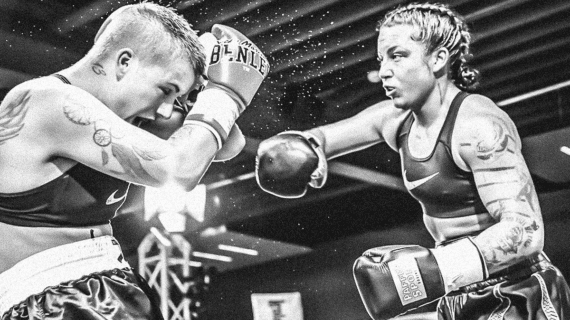

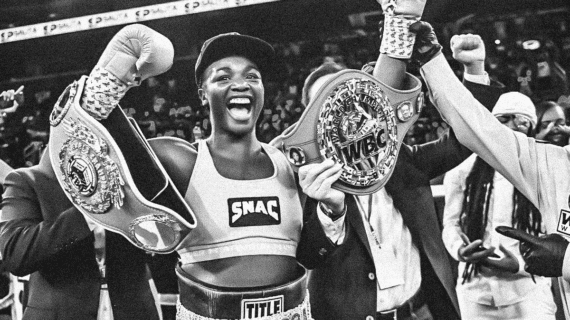

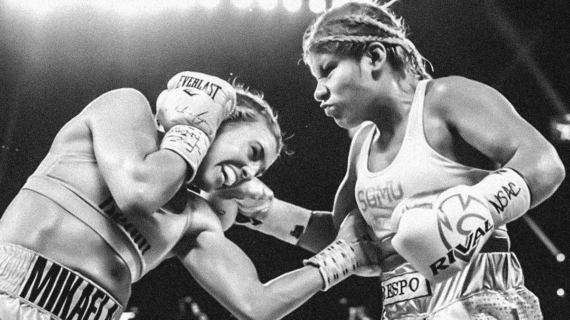

His entry into the major leagues? Ariane Fortin’s victory at the 2006 Amateur World Championship. “For me, it’s harder to be an amateur champion than a professional one. Professionally, you can avoid the best, wait, choose, and win a vacant title. Amateurs, you have no choice but to face the best.”

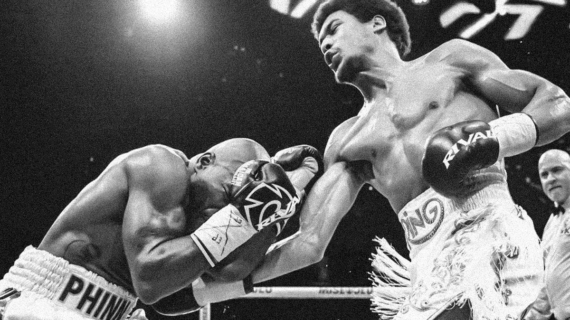

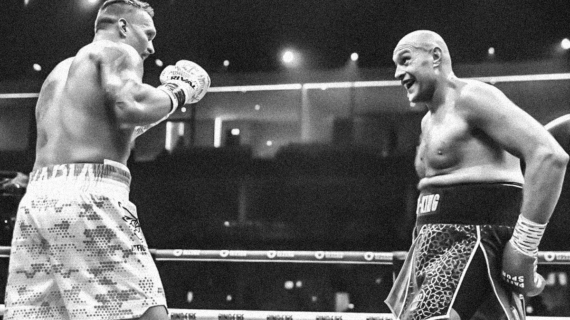

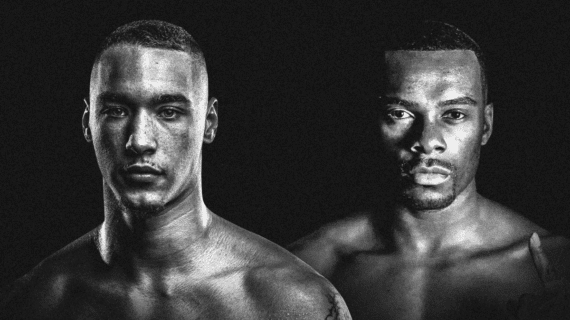

A fight he regrets? Without speaking of regret, he offers this analysis of the world championship fight between Dierry Jean and Lamont Peterson. “That night, he should have beaten Lamont Peterson, but Dierry, a bit like me, he liked to party…”

His greatest victory? It’s also the one he’s most proud of, because after the consecration came the confirmation with Ariane Fortin’s second Amateur World Championship in 2008.

His most stressful fight? The elimination bout between Dierry Jean and Cleotis Pendarvis in Miami. “He got cut in the 2nd round, and I told him, ‘You have to give it your all because it could go to decision after 4 rounds, and the fight is close…'” Five minutes later, a sigh of relief, Jean won by knockout in the 4th round.