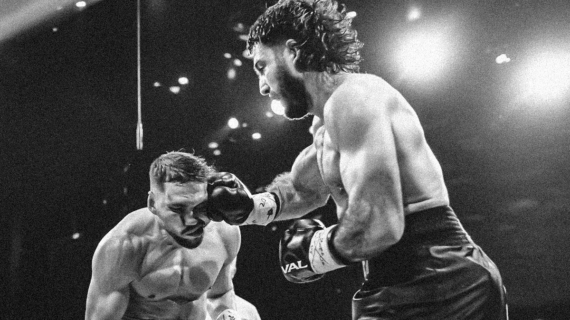

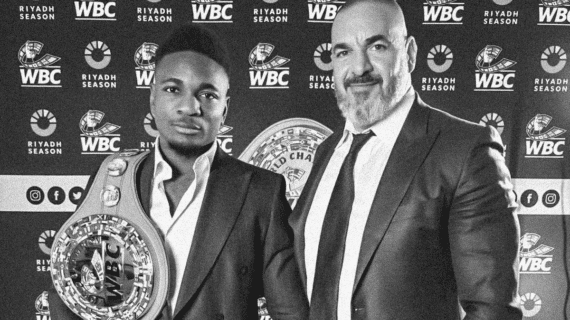

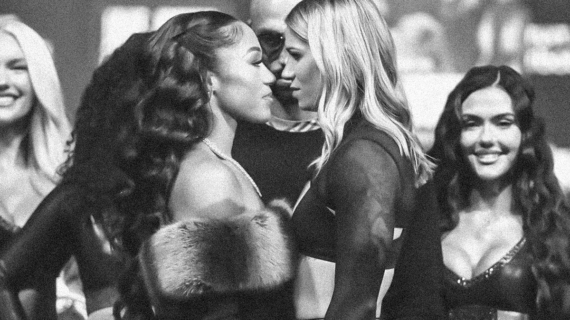

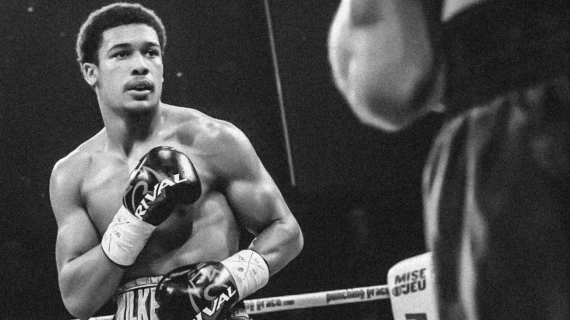

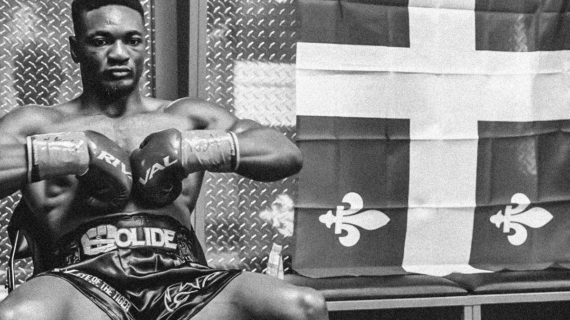

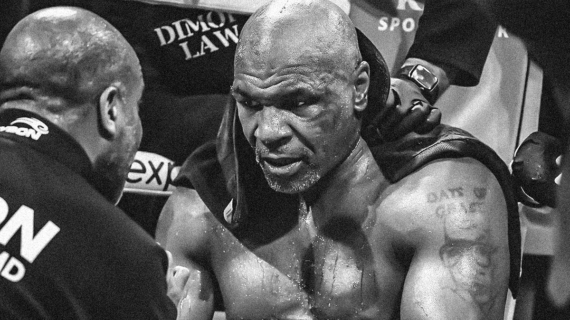

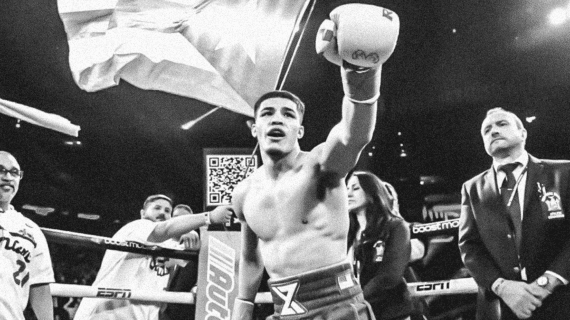

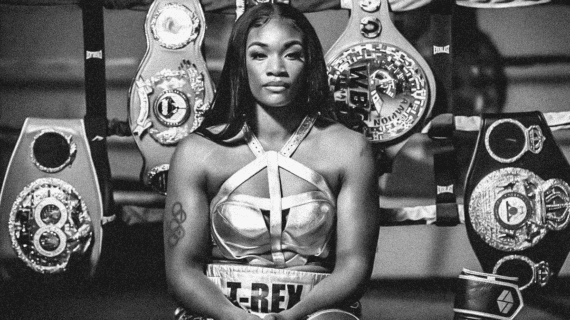

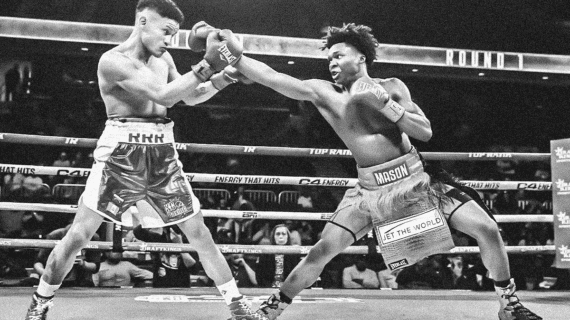

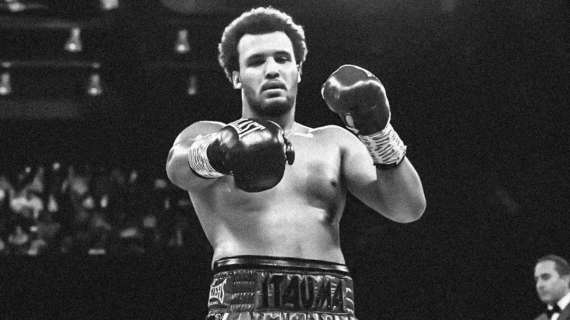

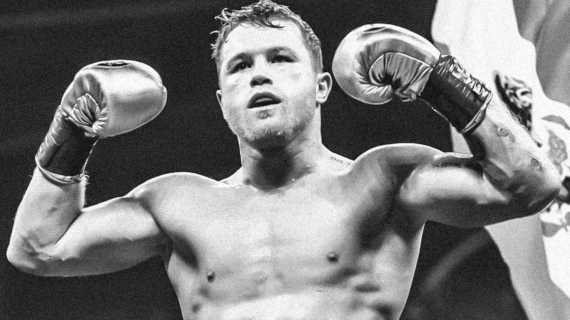

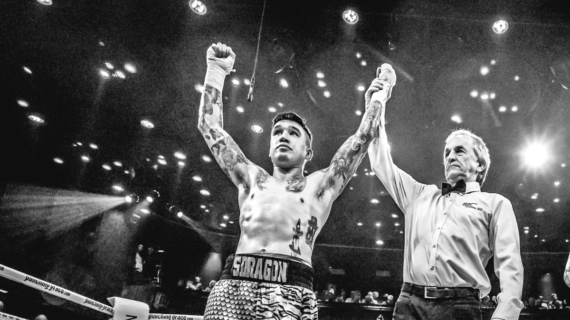

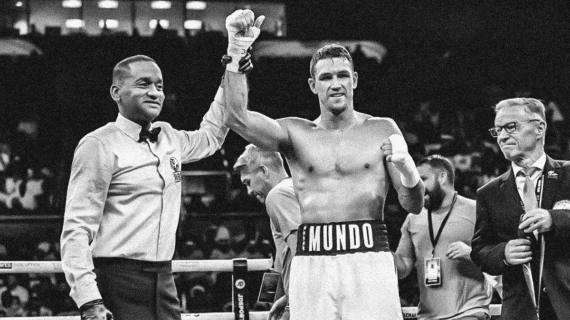

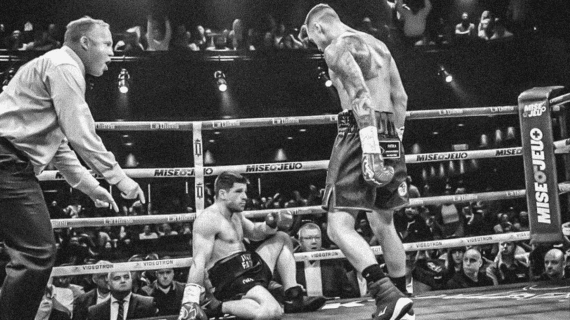

Photo: Cris Esqueda/Golden Boy Promotions | Canelo Alvarez (61-2-2, 39 KOs) proves to be too much crafty and powerful for the rising Jaime Munguia (43-1, 34 KOs) last Saturday.

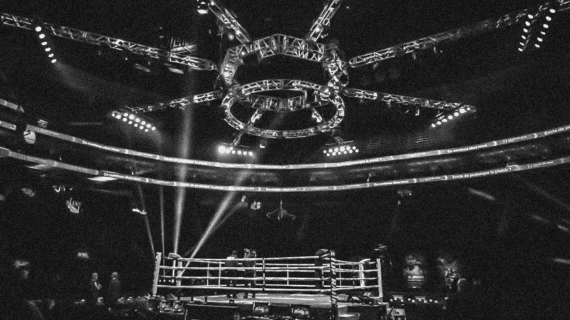

It was easy to take the extended Cinco De Mayo weekend for granted as boxing fans. For over a decade, it’s just been on our calendars that Canelo Alvarez will fight that weekend, and always in an event of significance. Naoya Inoue, similarly, has been one of the most active elite fighters in the sport for some time, so his appearance on Monday morning on the east coast might not have felt novel.

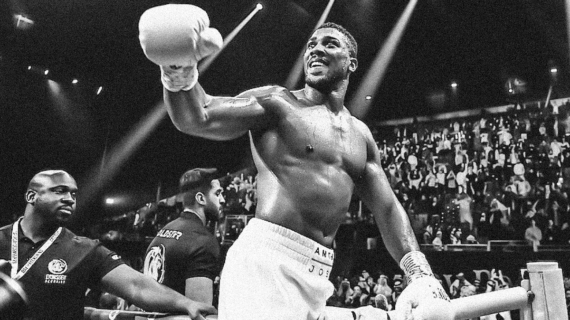

But years down the line, when we look back at our present era, Alvarez and Inoue will stand out as two of this time period’s best. Getting to see both of them fight in less than three days in major fights in raucous venues was a privilege we should appreciate while we have it.

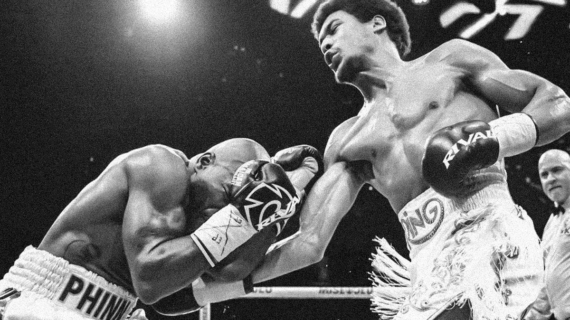

It’s a tired cliché that comparison is the thief of joy, but it warrants use in the sport of boxing quite often, as no sport loves to pillage its own shelves of happiness more often than the Sweet Science. In the wake of Alvarez and Inoue’s victories, a good amount of discussion has materialized seemingly rooted in ESPN commentator Timothy Bradley’s invoking of Sugar Ray Robinson and other greats on the Inoue broadcast.

The nature of sports talk has transformed over the past twenty years, changed forever by ESPN’s “embrace debate” era which correctly wagered that hypothetical argument was like catnip to fans, creating an economy of hot takes both from the broadcasters themselves and those watching, responding and chatting amongst themselves. One of the go-to debates that is sure to create ratings and clicks has always been “is (insert current athlete) greater than (insert legendary athlete,” intentionally pitting generations against one another. Turn on any sports channel for long enough, and someone will be debating whether LeBron James is better than Michael Jordan or whether Wayne Gretzky could score 50 goals in today’s NHL.

These types of debates are genius television and column tactics because no matter how much empirical or statistical evidence there is, there can be no definitive answer, only feelings and opinion. Both sides can always feel like they’re right.

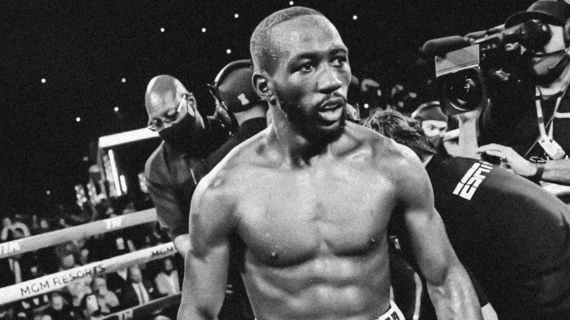

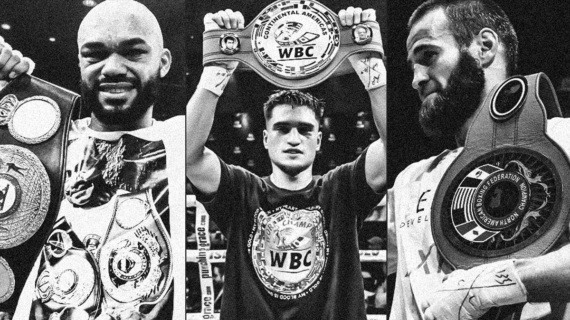

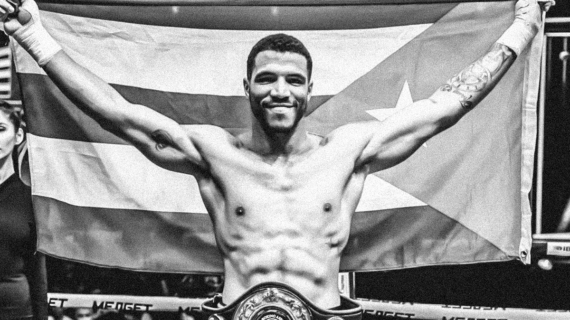

In Bradey’s case, to my ear, it didn’t sound like he was even comparing Inoue to Robinson or any other great head-to-head. Rather, he was pointing out what was objectively true: Inoue, along with Canelo and Terence Crawford, will likely be the first three names we mention from this time period when we talk about this era’s greatest fighters. Naturally, when these discussions start, they inevitably devolve into “(current fighter) couldn’t beat (retired fighter)” or “today’s fighters couldn’t hang in (insert previous era).”

In other words, there’s the implication that what you’re watching as a modern fan just isn’t that good.

I’m here to tell you: it is.

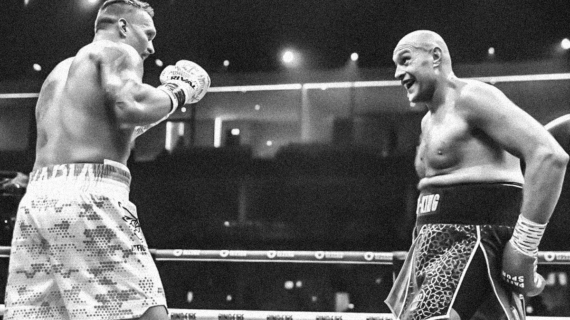

First, there’s the obvious–that athletes in every realm have improved physically over the years and that in every vocation, generations pass down techniques for them to be improved upon, making it a logical conclusion that today’s fighters are at least the best athletes we’ve ever seen in a ring. But secondly, why let the question of whether Inoue could have beaten Wilfredo Gomez or whether Canelo would have beaten Archie Moore take away from the enjoyment of watching greatness in real time? Athletes can only reasonably be compared to their actual contemporaries, and even then, in boxing with weight classes at play, comparisons can get muddled. But even with that being the case, fighters like Canelo and Inoue are indisputably special.

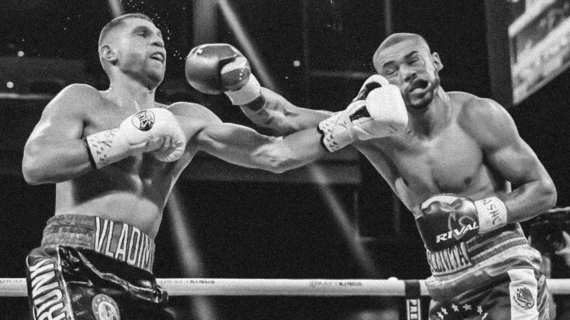

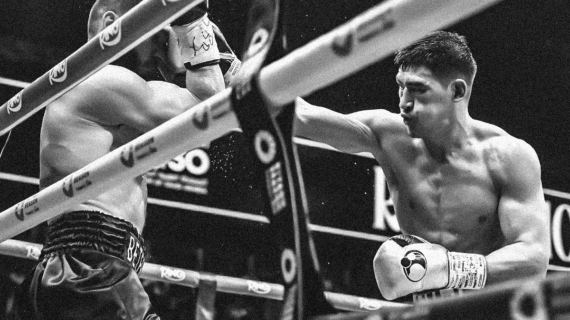

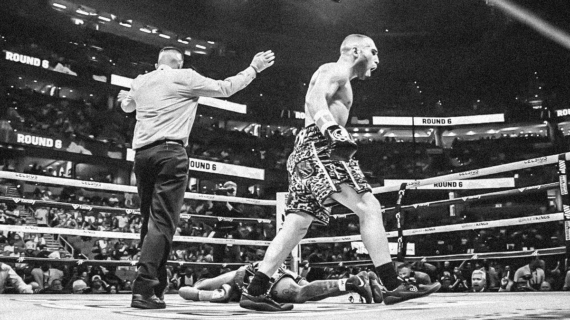

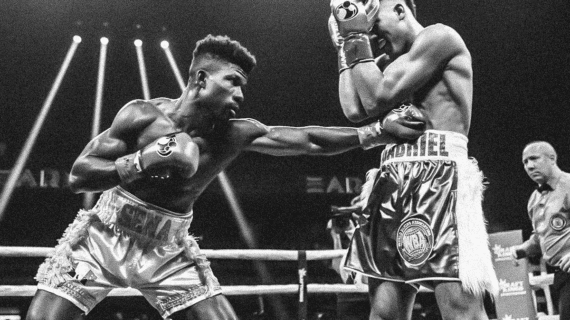

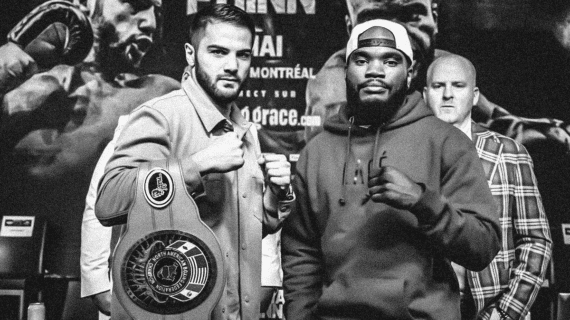

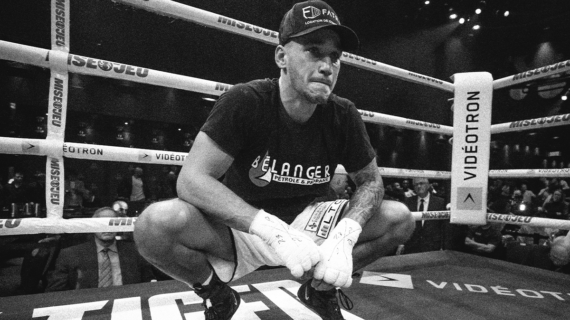

Canelo plowed through another legitimate Top-5 super middleweight on Saturday in Jaime Munguia. Munguia may have been a heavy underdog coming into the fight, but it speaks to the gap in skill between Canelo and the field that a fight against a man who would be favoured against 99% of the 168-pound men on the planet was a walk in the park, particularly after the picturesque fourth-round knockdown.

Although Canelo might have lost a step compared to say, the 2018 version of himself, this version of him remains a joy to watch, in part because of how he’s adapted his style. Through his years of ring wisdom, Canelo has crafted a style that at his age and new size at 168 pounds, can be replicable fight after fight, against almost anyone. It no longer serves him to be a buzz saw pressure fighter, his legs might not hold up to the rigours of being a pop-and-move defensive whiz, and it’s likely not wise to trade shots in a weight class he is relatively undersized in. So, he’s blended elements of all of those approaches, creating an air-tight defence that he can establish at mid-range and judiciously throw almost exclusively power shots.

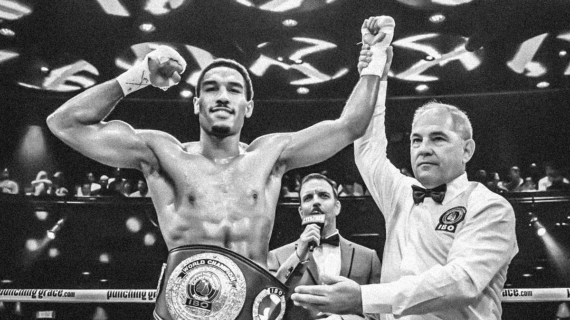

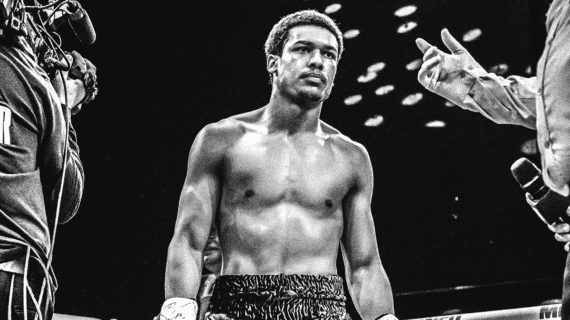

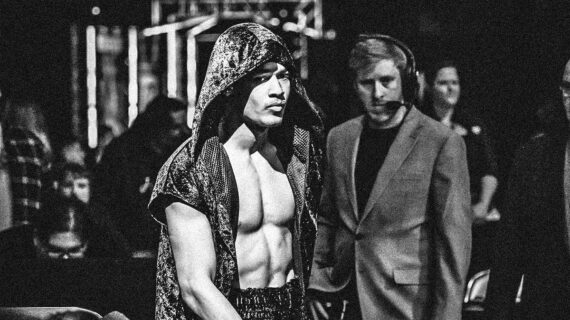

Fans of a certain age have been able to literally grow up with Canelo watching him on television, and his adaptation to age mirrors their own. Watching Inoue is a different experience. Although he’s 31 years of age, there has been no noticeable decline in his skill or athleticism whatsoever. Rather, he is one of the exceptionally rare fighters that does not have to negotiate between speed, power and accuracy when he throws a punch. When he lets a punch go, he can be sure that it’s fast, powerful, and it will likely hit its mark.

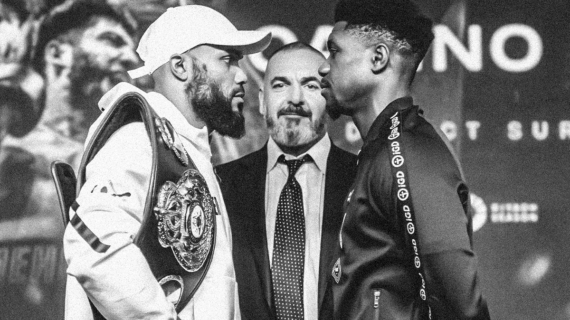

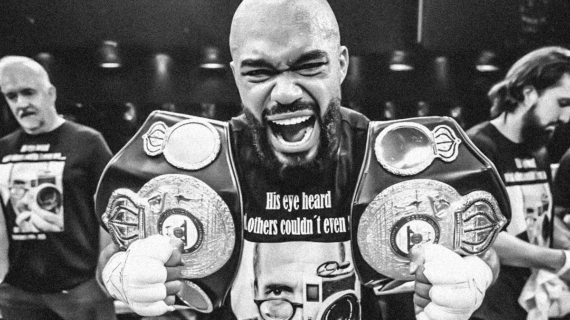

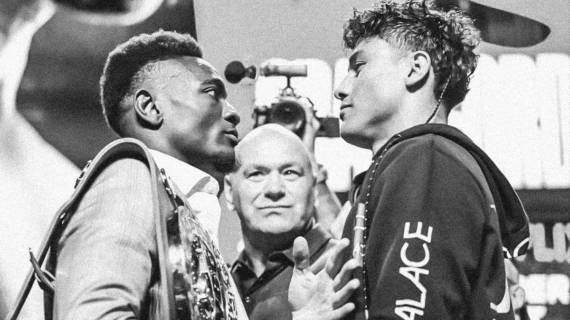

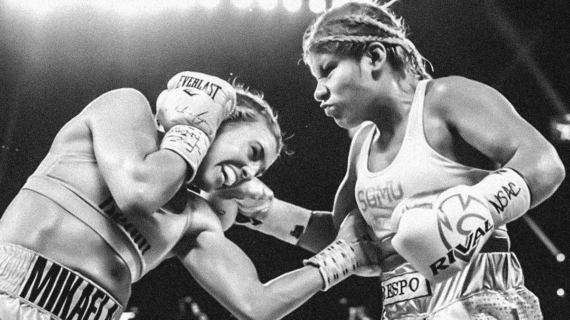

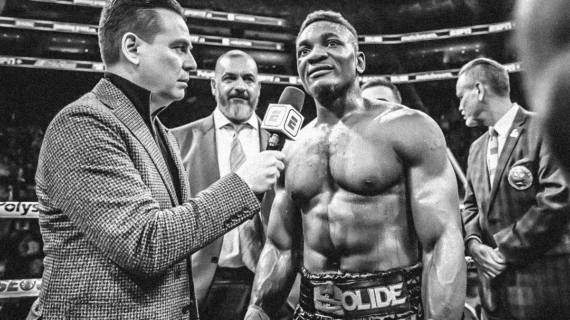

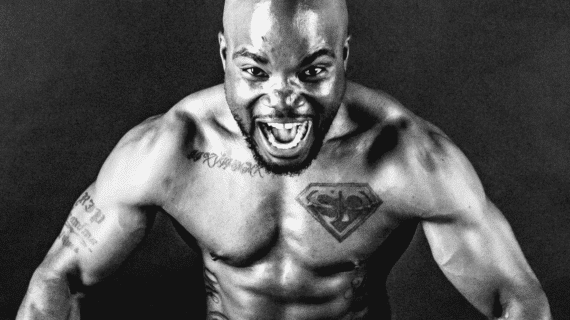

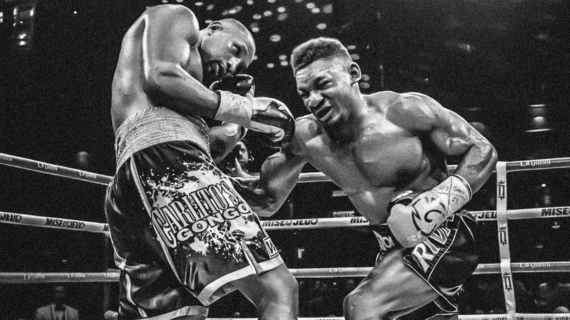

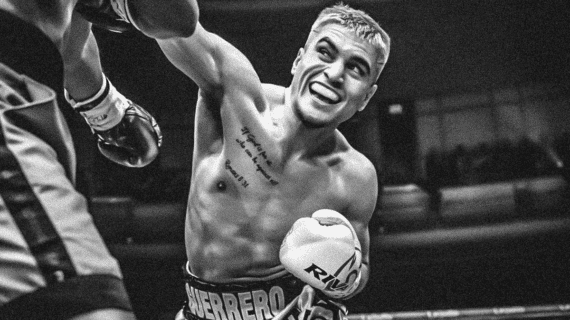

Inoue did face some adversity against Luis Nery, getting dropped in the first round. However, the knockdown seemed only to wake up The Monster. Perhaps fuelled by Nery’s sneering heel attitude throughout the fight buildup, or the 55,000 fans in the Tokyo Dome, Inoue showed a mean streak and an outward confidence he hadn’t shown before. He smiled at Nery, he taunted, he showboated, he generally flaunted the embarrassment of riches that is his offensive arsenal. He fought like a fighter who knew a knockout was coming, which again, is an astonishing feat to be so certain—and ultimately correct—of your superiority over the No. 3 fighter in the division that you pull out bolo punches two rounds after hitting the canvas. Inoue has always been The Monster, but now he’s behaving like one too.

My advice to boxing fans is this:

Never stop watching and studying old fights and fighters. There is more footage and writing to consume than you have time left in your life, and there are many joys to be discovered and much to learn by turning back the clock. But don’t let people convince you that what you’re watching today isn’t great either. One day we’ll look back on Canelo and Inoue and others the way we’re already fondly looking back at the fighters of the 90s that writers also dismissed while comparing them to fighters of yesteryear. Why wait to appreciate them when you can just do it right now? One of the beauties of sport is being able to appreciate mastery in real time. Why rob yourself of that?

As another famously debate-adverse man in J. Cole once said: ‘You ain’t never gonna be happy ’til you love yours.’