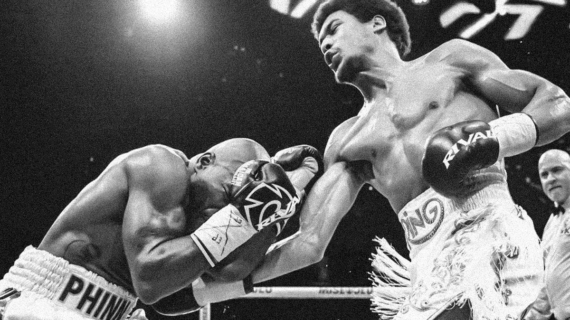

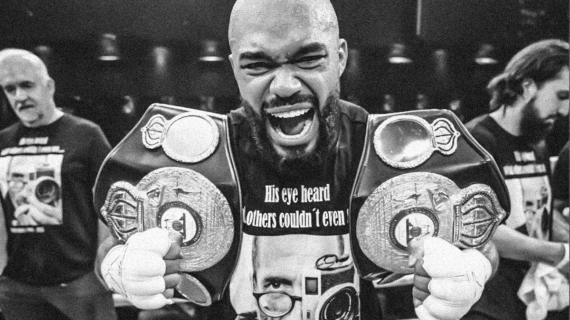

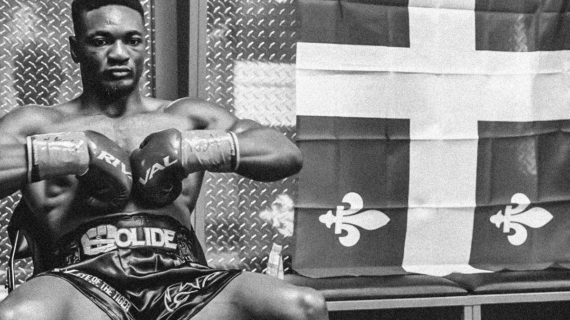

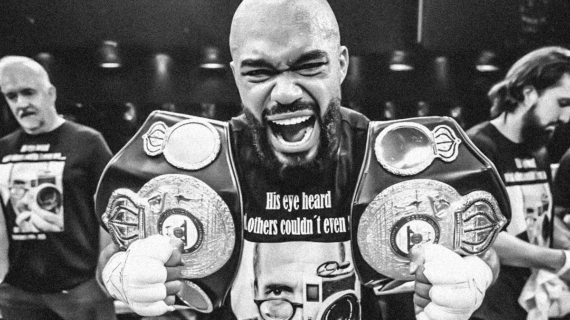

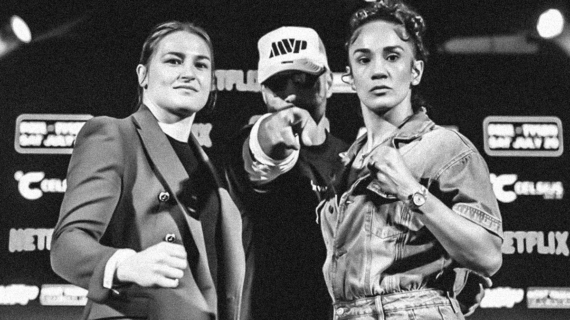

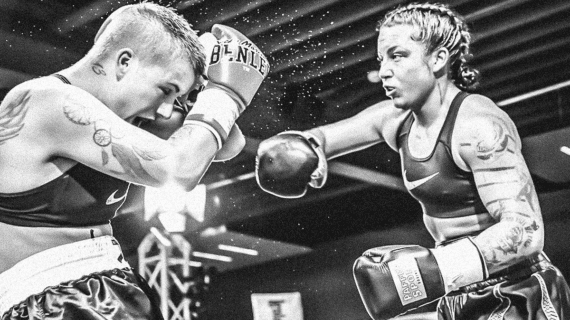

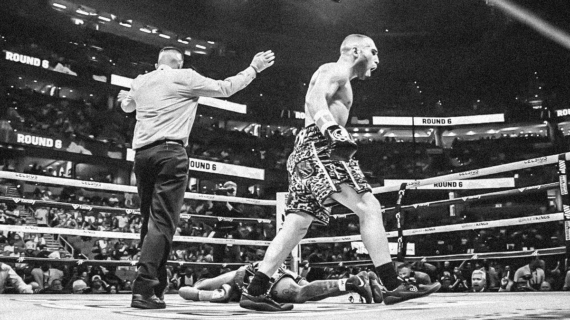

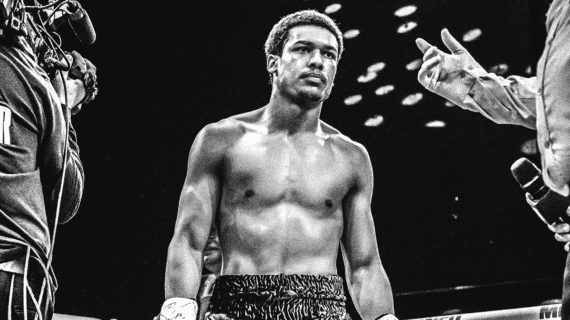

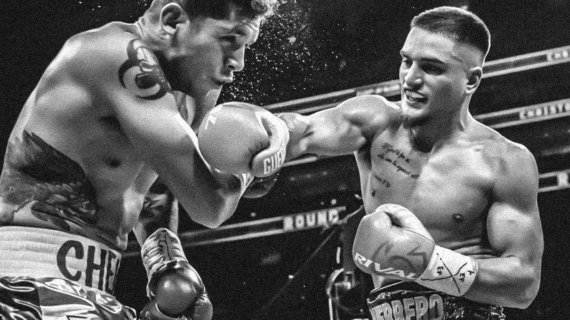

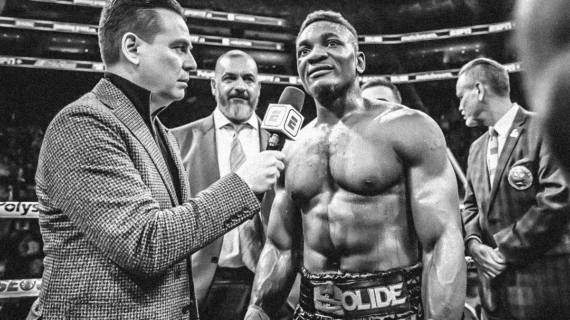

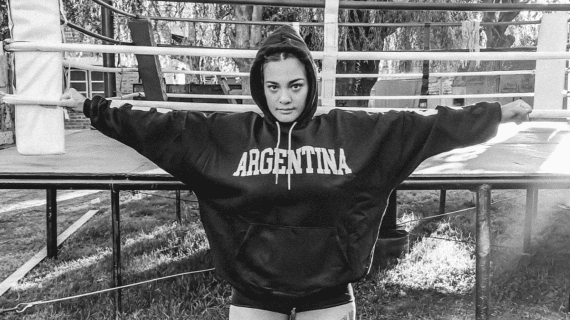

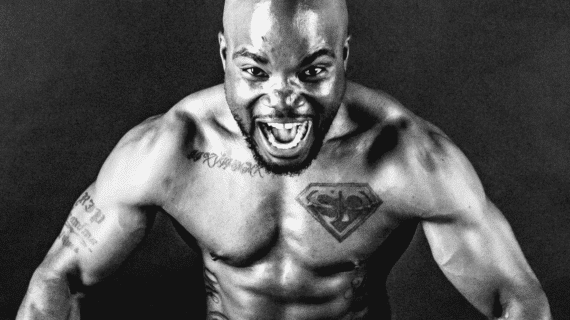

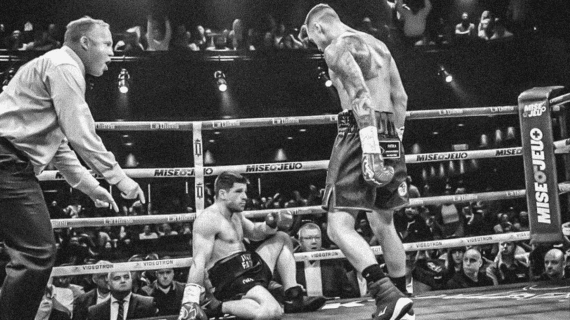

Photo: Vincent Ethier – An image can say a thousand words, and this one says a lot about how Arslanbek Makhmudov has come back on May 25th.

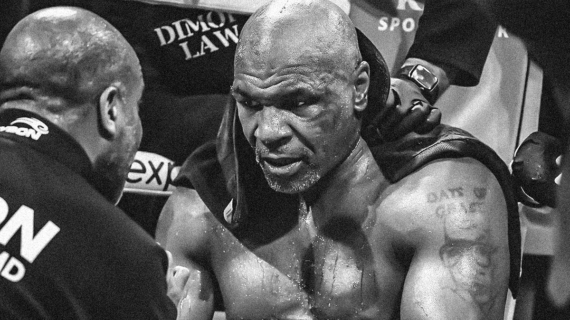

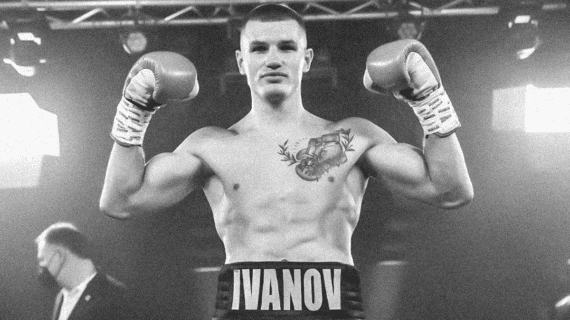

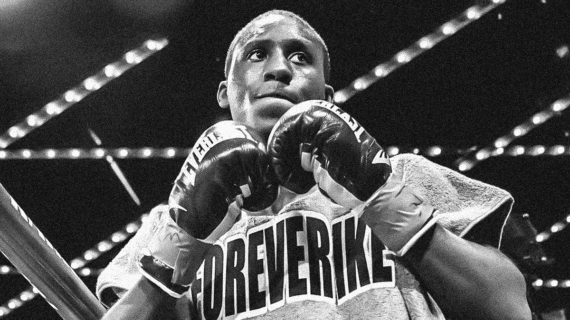

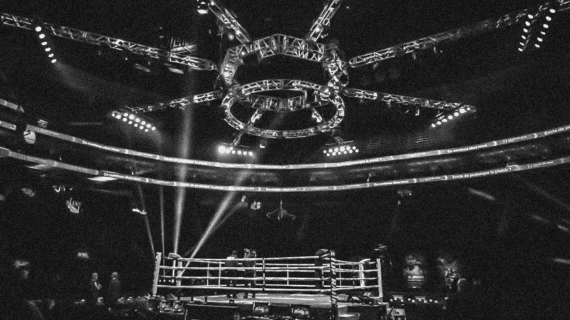

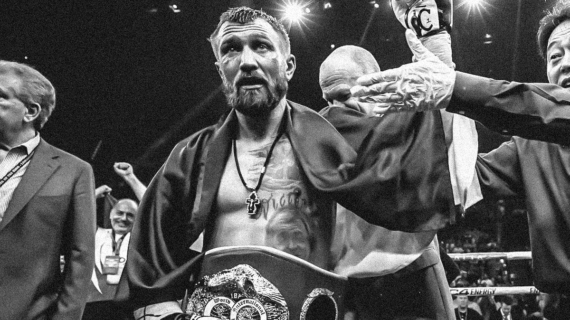

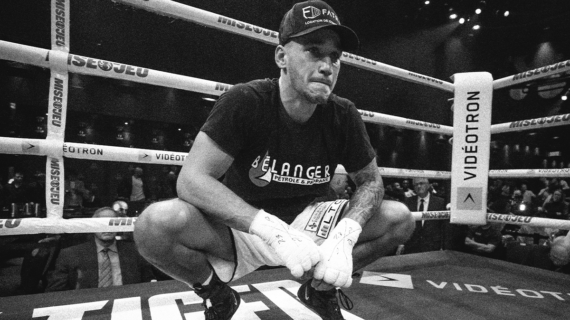

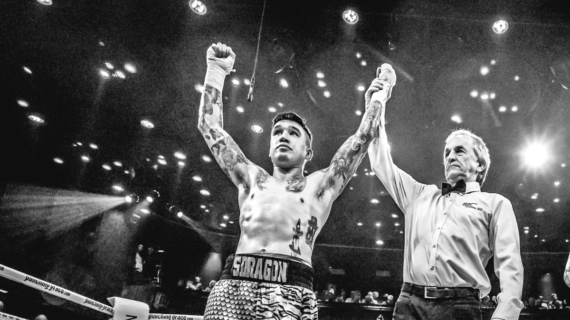

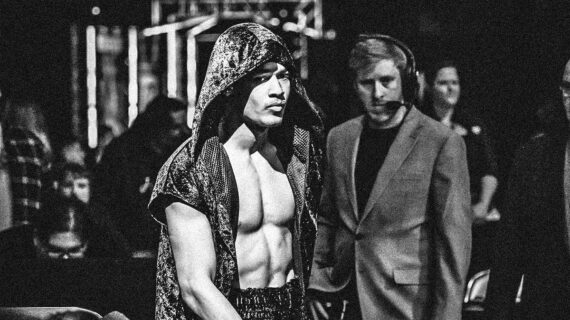

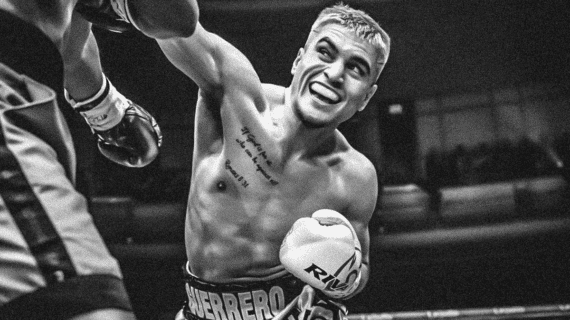

As Arslanbek Makhmudov walked through the curtains at the Centre Gervais Auto, there was no sign that anything was different about him. The air raid siren that he uses in lieu of entrance music still howled, his furrowed brow still arched at a menacing angle as he intimidatingly cracked his neck like a cartoon bully ready to lay a beat down on their latest victim. After he stepped over the top rope and the action began, there was also no sign that anything was different about him—for better or for worse.

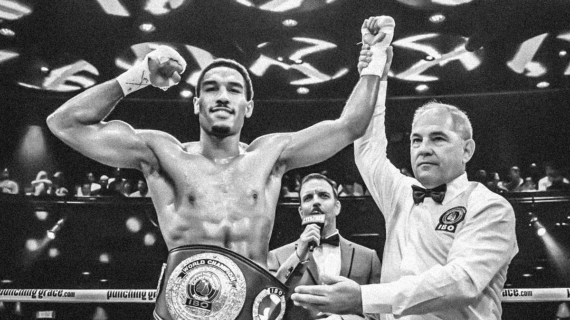

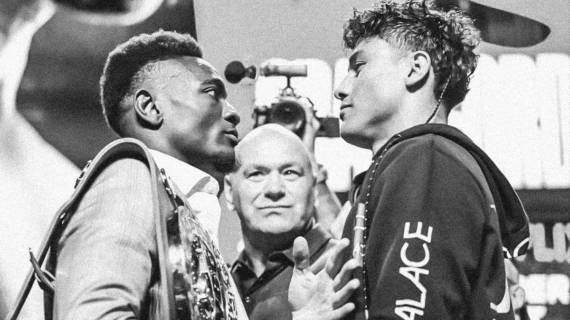

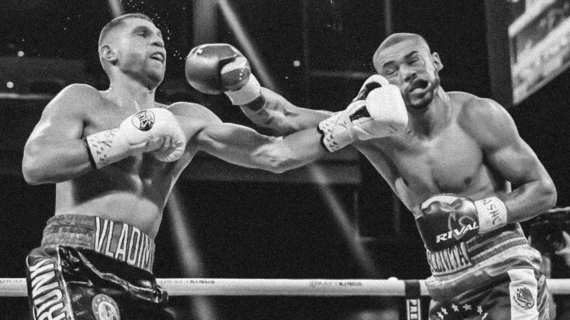

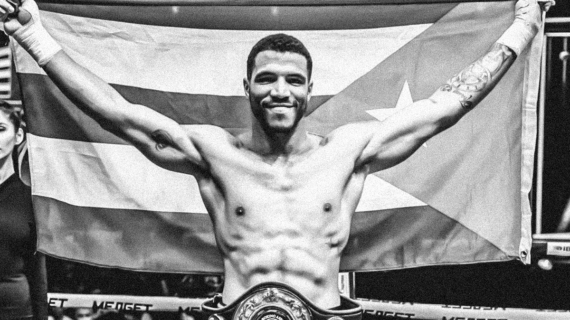

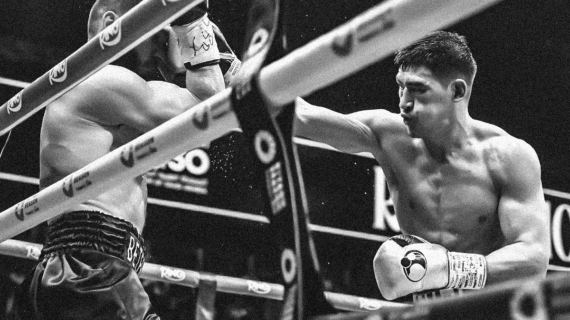

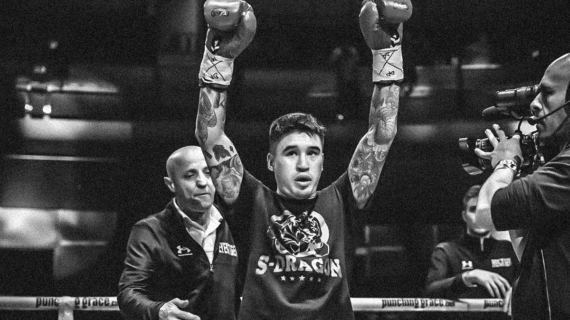

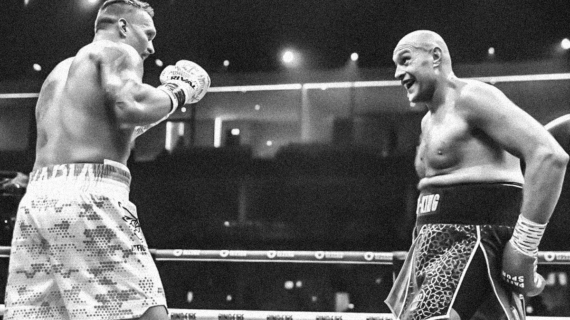

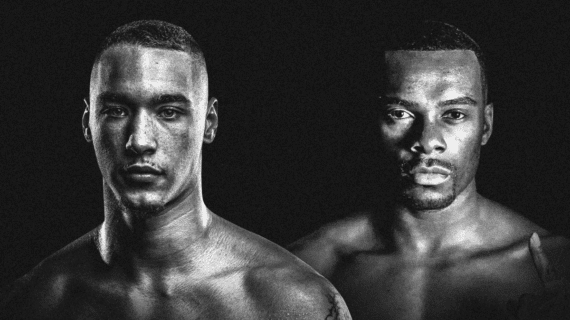

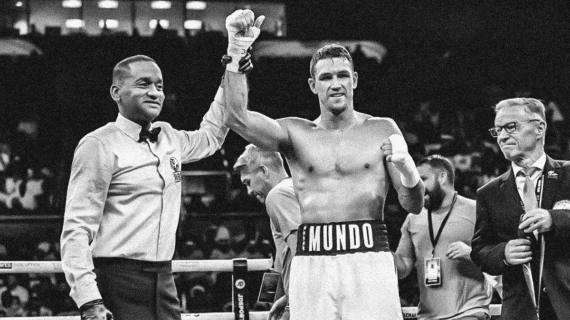

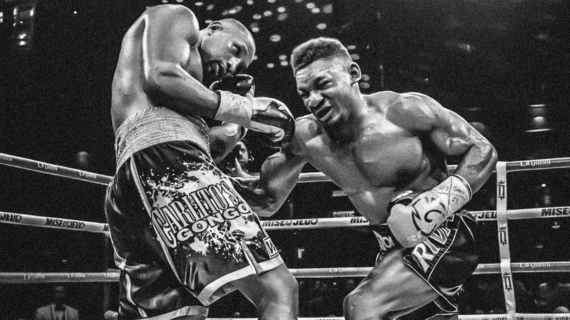

Makhmudov bounced back from his shocking knockout loss at the hands of Agit Kayabel last December with a second-round KO win over Miljan Rovcanin in the co-feature of Eye of the Tiger’s Punching Grace/ESPN+ offering on May 25. “The Lion” mauled his prey early and nearly sent Rovcanin into my lap at the ringside commentary table with a right hand in the first round. In the second round, he settled into less of a brute force game plan, and lined up a right hand that left Rovcanin flat out for the final count.

There was certainly no sign of hesitation from a fighter that had been stopped in his most recent outing. If anything, there was a sense of anger, a sense that someone had to pay for the humiliation he felt, and on this night, it was Rovcanin (rather than Junior Fa, his original opponent, who chose to walk away from the sport for ethical reasons). Makhmudov looked like a fighter who was hungry not just for retribution, but eager to get back on the level he feels he belongs at.

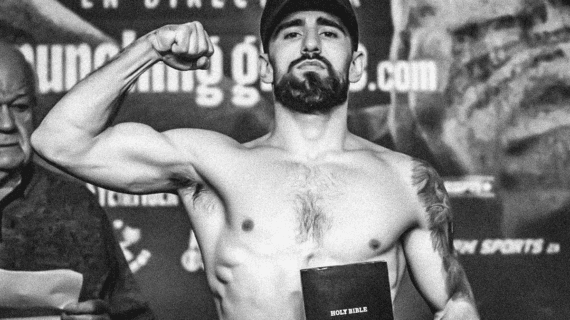

Makhmudov’s loss last year, one of the biggest betting upsets of the calendar year, came with an additional blow, but also a caveat, a broken right hand suffered early in the fight. The boxing public largely has not attributed the loss to the injury in any way, but Makhmudov certainly does.

“In the third round he did his job good with a body punch and finish the fight [in Round 4] but for me it’s a good experience. I fight with broken hand for three or four rounds,” Makhmudov told The Ring’s Anson Wainwright. “Honestly, I know myself, this guy isn’t at my level, he’s not a bad record. Look at his record, he did 23 fights, half his fights he didn’t fight with anybody and couldn’t knock them out and some were close. You think I’m worse than this guy? Of course not!”

Fighters rationalize losses in all sorts of ways, some rooted in reality, some very much not. The validity of those self-explanations doesn’t always matter. Any number of fighters who have lost a fight have a crudely formed explanation for why it shouldn’t have happened, and any number of fighters have bounced back from it anyway. Makhmudov’s broken hand may have been the primary reason for his stoppage loss, but it also may not have been. In either instance, Makhmudov seems to fully believe that the result against Kayabel was flukish—or at least that’s what he’s chosen to express publicly.

Hearing fighters react to a loss in the manner Makhmudov has prompted a reaction that is two-fold. On one hand, it makes one question whether the deeper root causes of the loss are actually being addressed. Does the fighter think they can do the exact same thing they’ve always done and return to success? On the other hand, it shows an unflappable level of confidence that is necessary for overcoming athletic trauma.

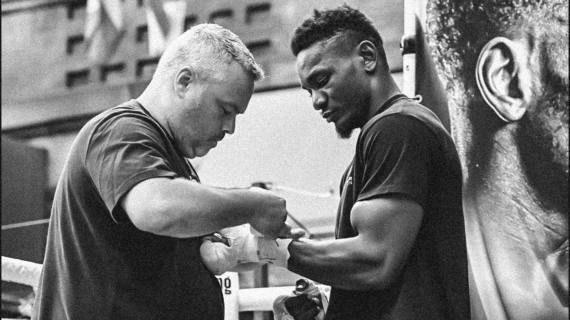

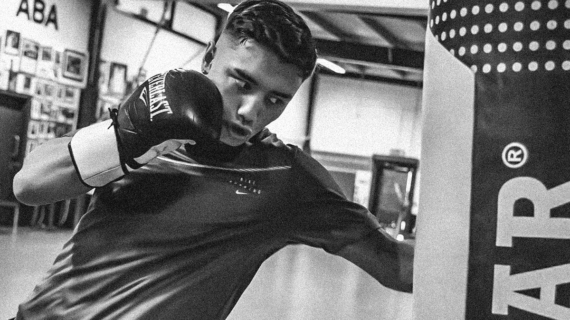

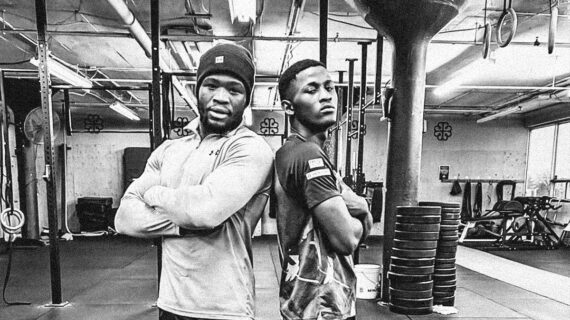

In Makhmudov’s case, his camp has admitted that he was “relying too much on one tool,” that being his otherworldly power. His change of tactics, however brief, in the second round against Rovcanin, was a suggestion that perhaps there’s a more boxing-conscious approach within him that he could tap into in future fights, one that he cultivated during a sparkling amateur career in Russia.

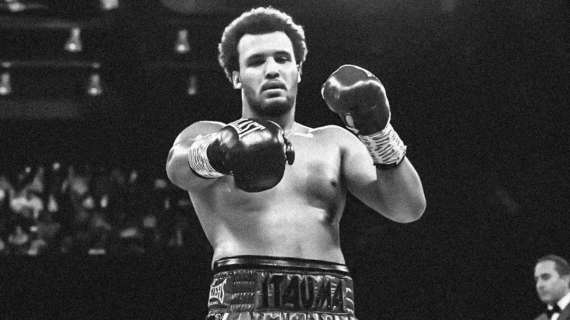

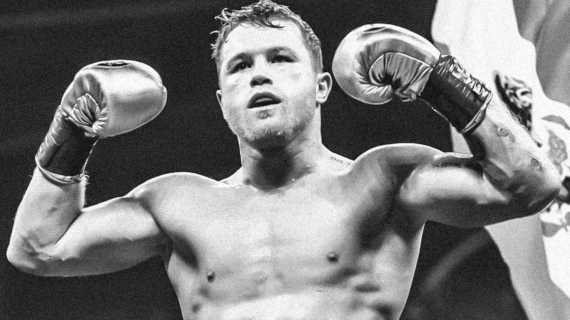

The reality is that knockout losses happen with more frequency in heavyweight boxing, more often than in any other weight class, statistically. Knockout losses to world-class heavyweights can indeed be the indication of a career derailed, or they can ultimately be a non-factor in a fighter achieving their peak. Greats such as Lennox Lewis, Evander Holyfield, George Foreman and more suffered knockout losses well prior to some of their finest hours. For others, like Michael Grant or Gerry Cooney, presumed would-be heavyweight champions, it was a sign that their peak had already been reached, and a precursor to darker days.

Coming back from a knockout loss remains a balancing act between regaining stoic self-belief, but also the self-awareness of what it was went wrong. To put it more simply: Maintaining your identity while acknowledging one’s mistakes.

In Riyadh?

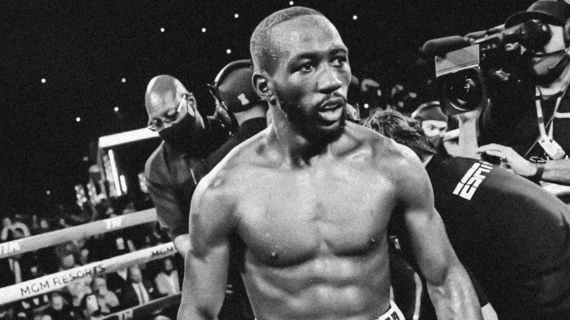

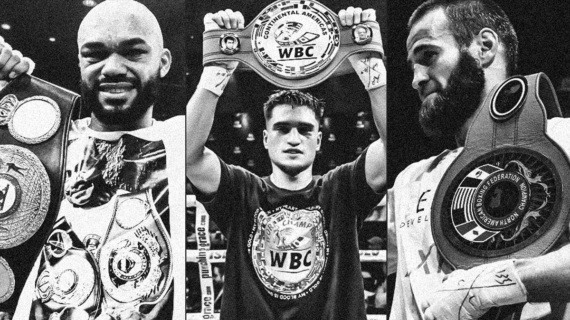

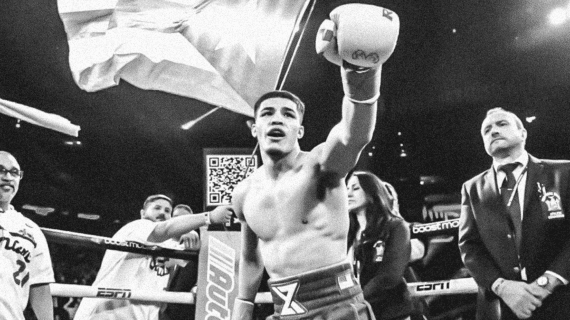

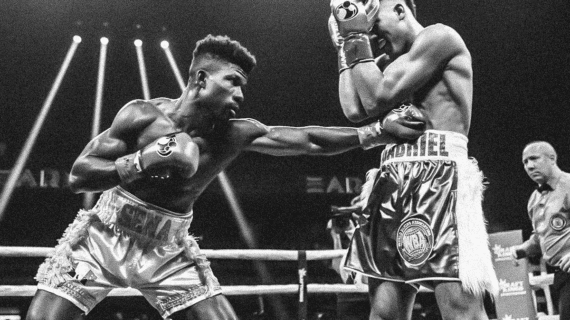

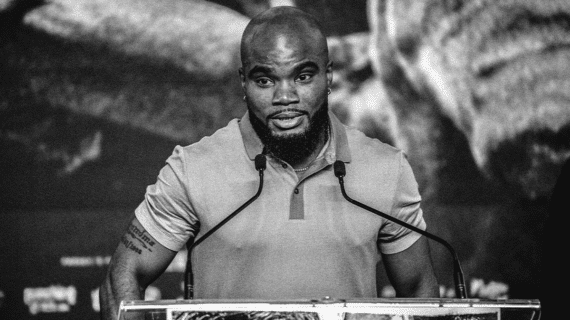

Amidst the mystery that is Makhmudov now, one thing is certain: He’s eager to find out who he is. Promoter Camille Estephan has expressed the desire to return to Saudi Arabia for Makhmudov to face another name-brand heavyweight, of which there are many available. Makhmudov remains ranked in the Top 15 by two sanctioning bodies, the IBF and the WBC. Of course, there is an undisputed heavyweight champion in Oleksandr Usyk, but his undisputed status will likely be fractured shortly, and has already in some respects. Daniel Dubois picked up an interim version of the IBF title with a win over Filip Hrgovic last weekend, making him perhaps the dream realistic target for Makhmudov at the moment.

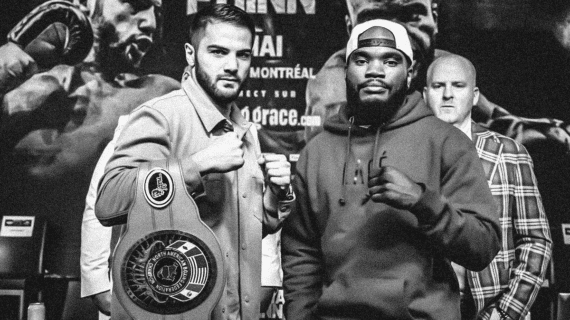

More Realistically

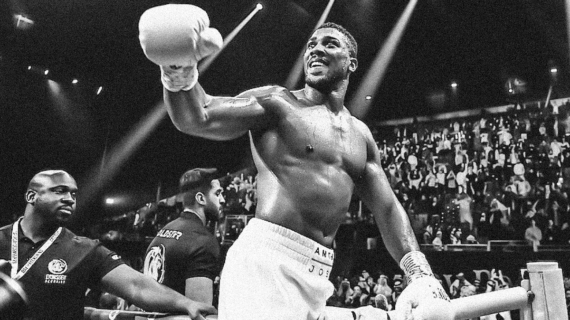

However, Makhmudov could find himself targeting other heavyweights who themselves have taken losses of late in a “thinning of the herd” type matchup. Jermaine Franklin has won two straight since his back-to-back losses to Anthony Joshua and Dillian Whyte, and is signed to Salita Promotions which is historically open to working with any promoter. Frank Sanchez, who also suffered an injury in (or before) his own loss to Kayabel, remains highly ranked and viable. Names like Otto Wallin, Joe Joyce and even Guido Vianello, Sergey Kuzmin and Michael Hunter fit many of the same descriptions—looking to re-climb the ladder, ready and available.

‘The Aura’

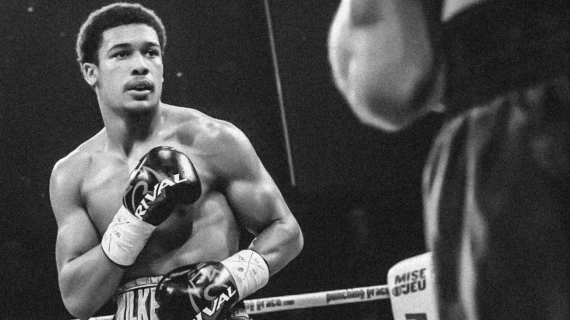

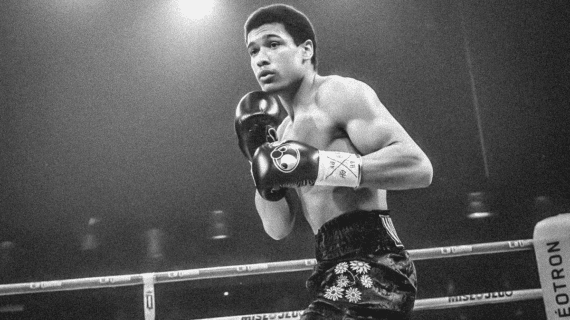

In addition to regaining his status in the division, Makhmudov is also fighting to regain the aura he once had. Few heavyweights over the last ten years or so have enjoyed the cult-like following that Makhmudov gathered during his developmental years as a professional. For many fans, Makhmudov was not just entertainment, he was a cause of sorts. The heavyweight who didn’t win Olympic medals like Tony Yoka or Joe Joyce or Filip Hrgovic, but rather their contemporary who would ultimately be revealed as the best of the bunch. Makhmudov can’t go on an undefeated warpath like perhaps some had dreamt, but the possibility of him being the best of his class is still very much within reach, as is the possibility that he becomes much more.

As they say, the breath of a wounded lion is more terrifying than its roar.