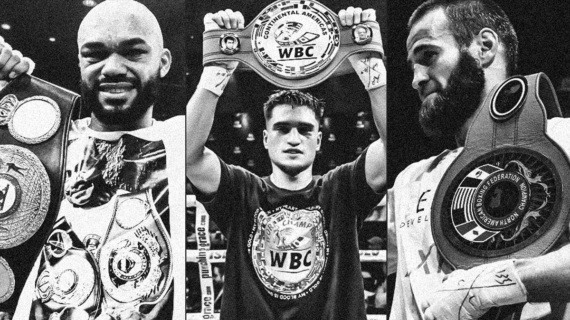

Some say they’re alike… “journeyman,” “opponent,” “gatekeeper”… but these are three very different realities.

It’s important to distinguish the journeyman from the opponent, sometimes wrongly called a punching bag, a bum, a taxi driver, or a tomato can.

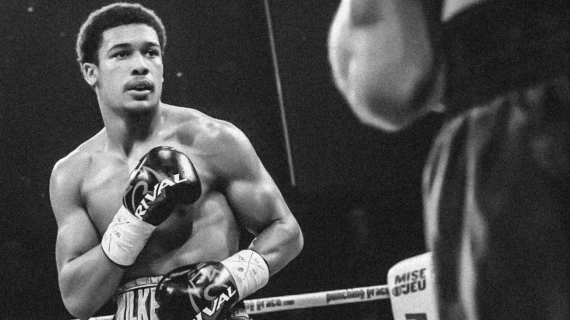

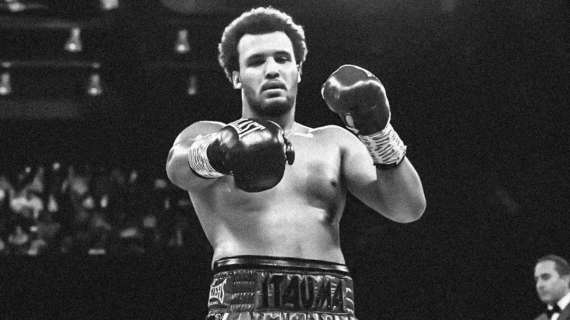

The journeyman is a seasoned professional, a tough fighter capable of putting up an honest fight, taking a young prospect into unfamiliar waters and forcing him to adapt. He knows the trade, knows how to survive, slow down the pace, frustrate, clinch, counter. He is a real test — he shows us what the prospect is truly made of.

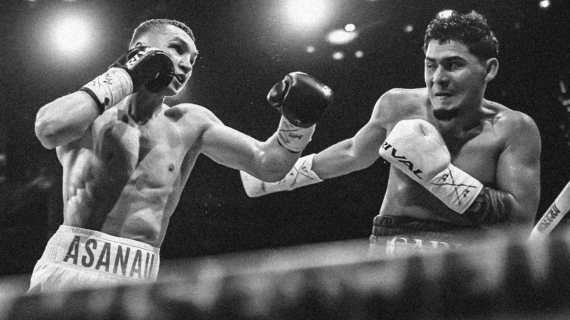

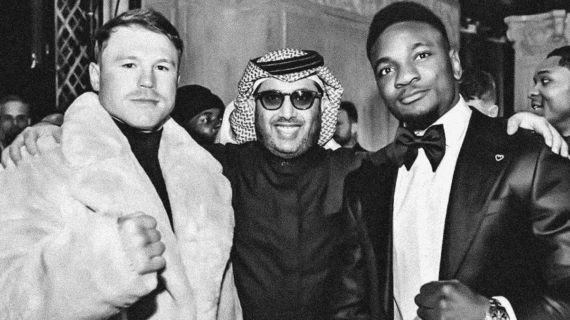

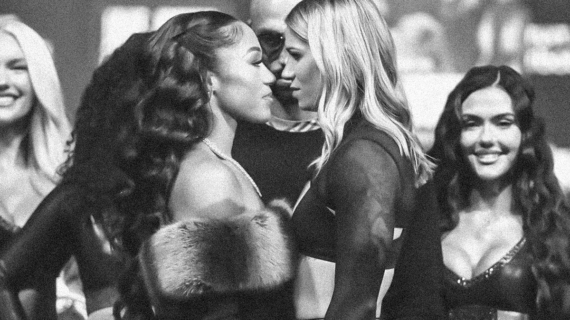

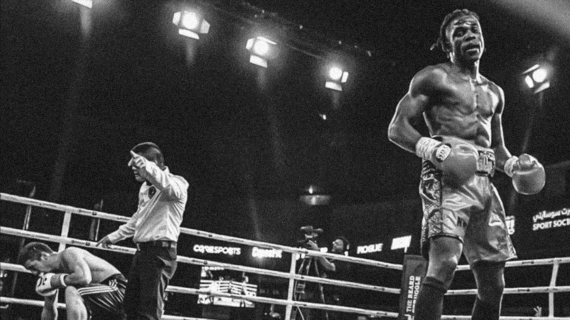

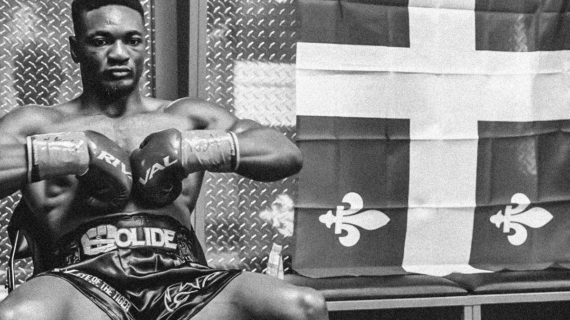

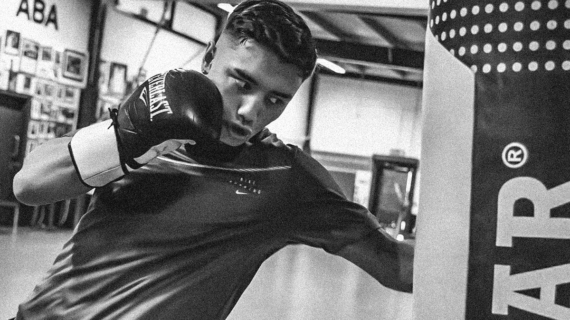

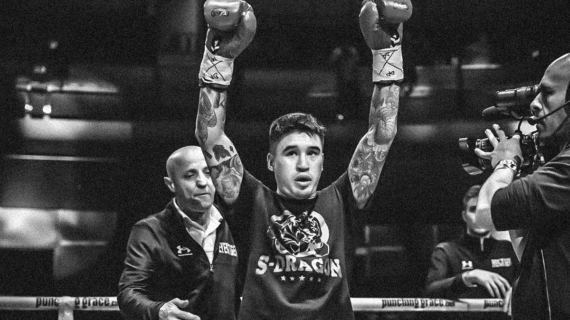

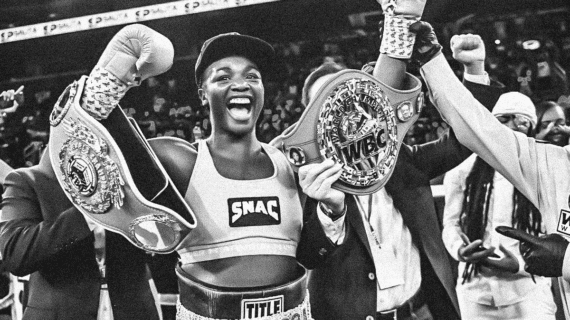

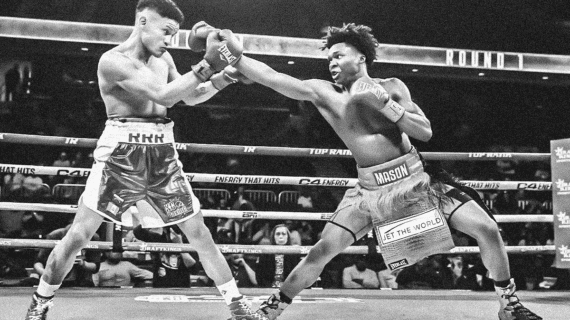

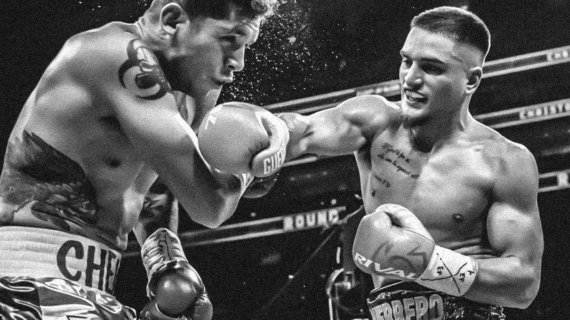

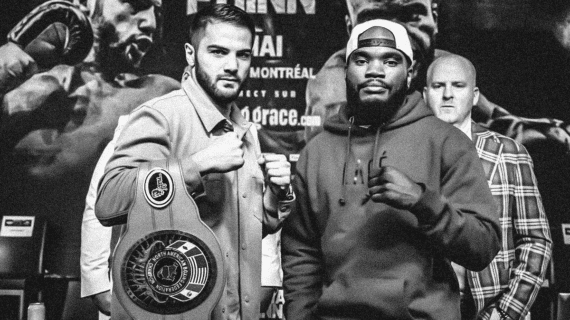

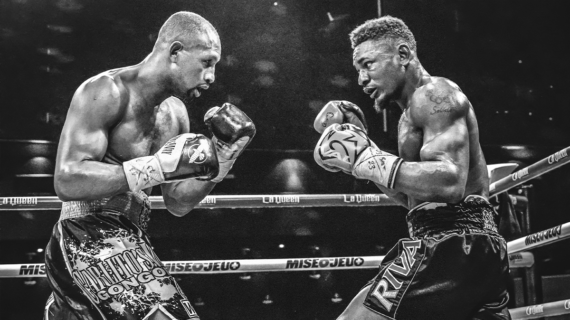

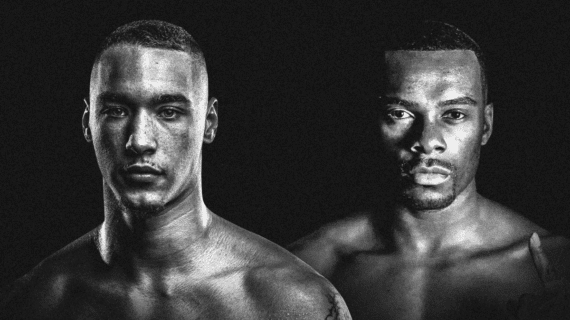

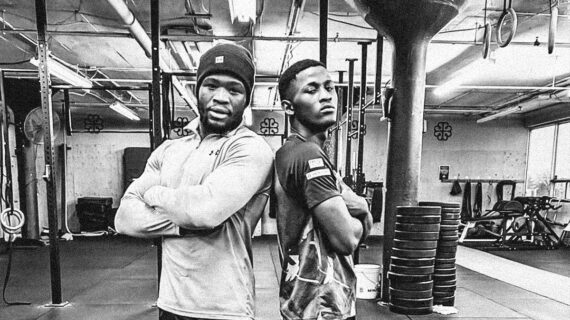

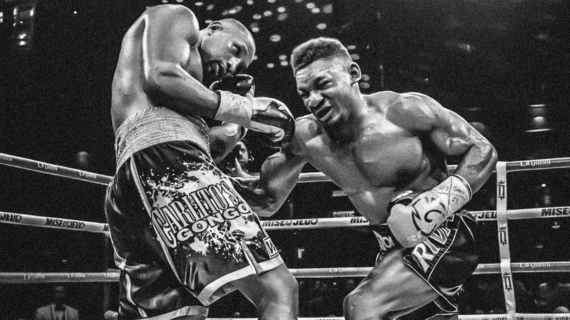

Photo: Vincent Ethier – Alexis Gabriel Camejo

By contrast, the opponent is a boxer thrown into an unbalanced fight, often poorly matched, out of shape or inexperienced, whose role is simply to make his opponent look good. There’s a fundamental difference here: the journeyman is a challenge; the opponent is a spectacle without real opposition. One elevates the sport. The other puts it to sleep.

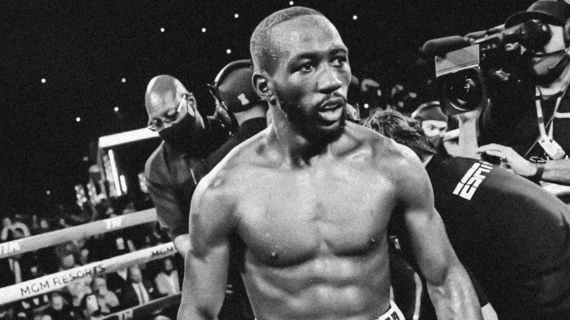

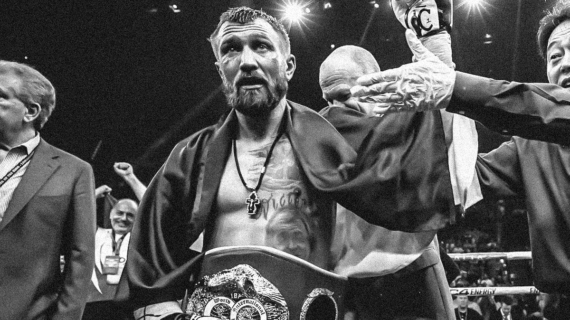

There is also a third important category: the gatekeeper. We’ve already spoken about him in another article. Unlike the journeyman, the gatekeeper is an established boxer, often ranked at the world level, who is no longer in the race to become champion but still remains a serious test for those aspiring to the elite. Beating a gatekeeper is crossing a legitimate threshold toward the highest ranks. Losing to him is no shame. It shows there’s still work to be done.

The journeyman is neither a stepping stone nor a background figure: he’s the guardian at the threshold, the one who says to the prospect: show me what you’re really worth. In the progression of a boxing career, one first faces opponents, then journeymen, then gatekeepers — before aiming for the top. Each has a role. Each is useful. But not all are equal.

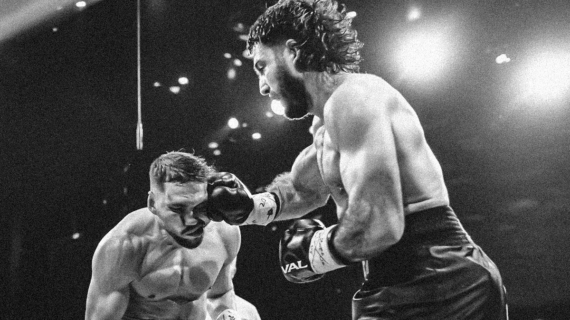

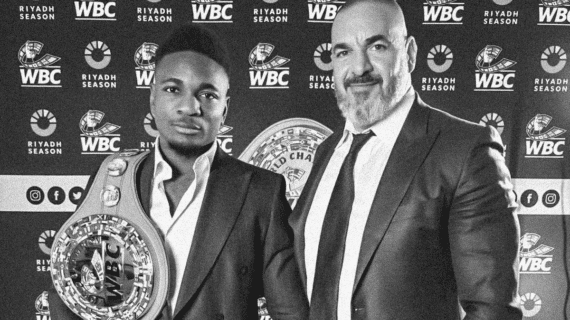

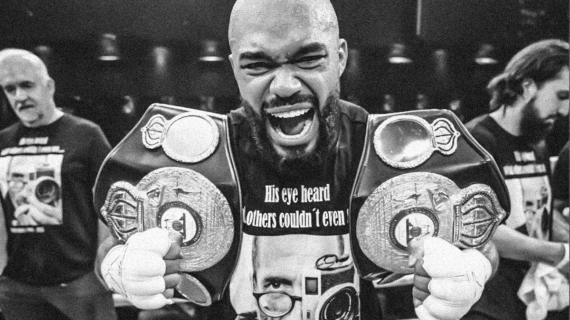

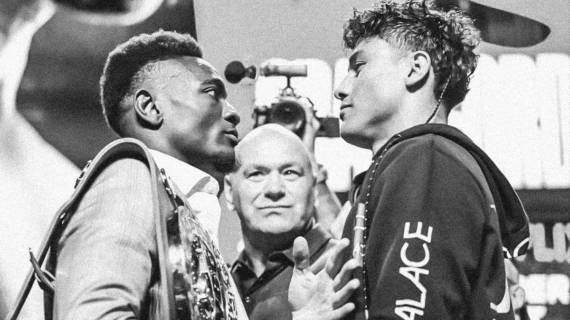

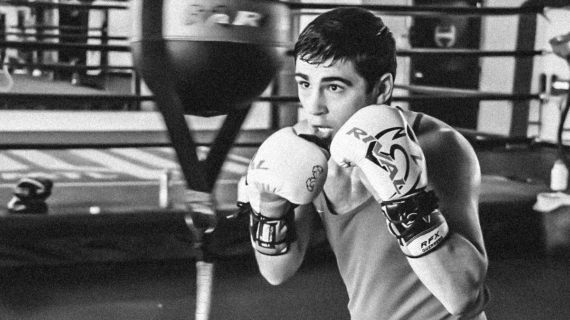

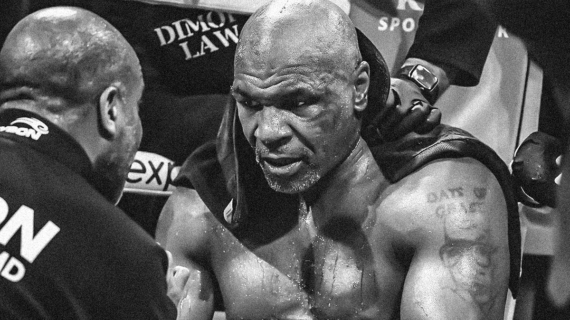

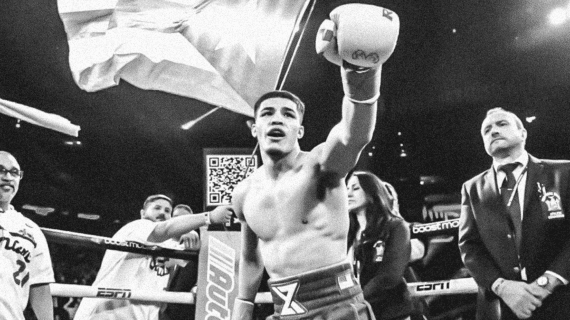

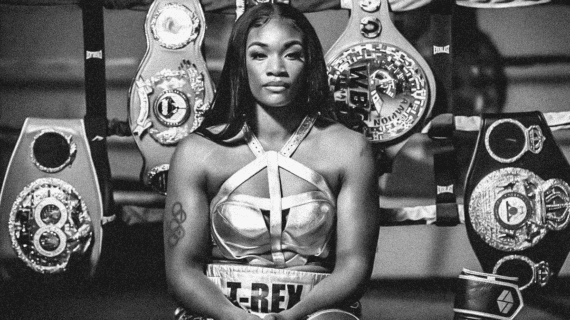

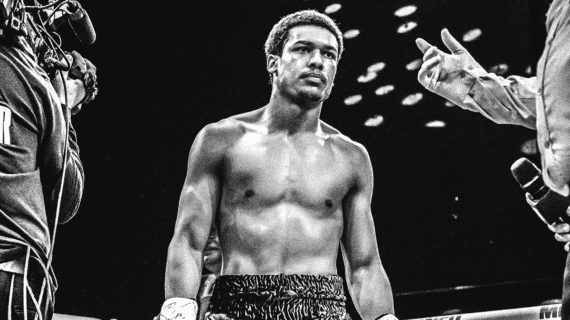

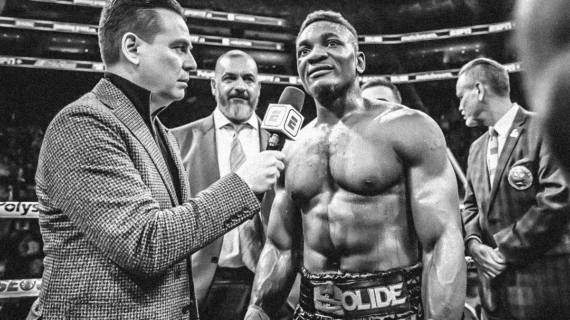

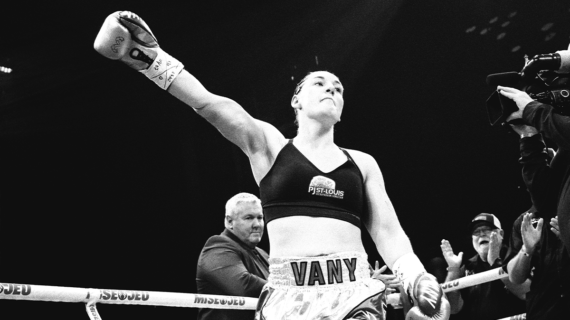

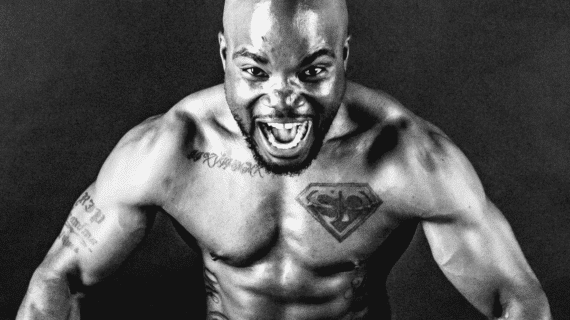

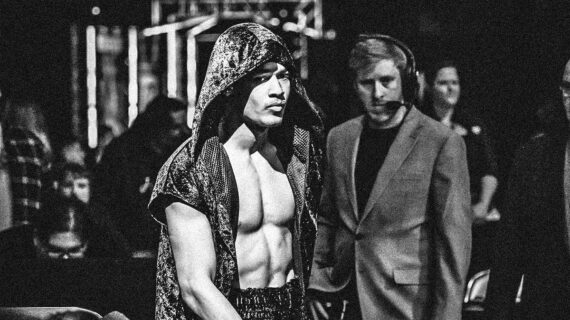

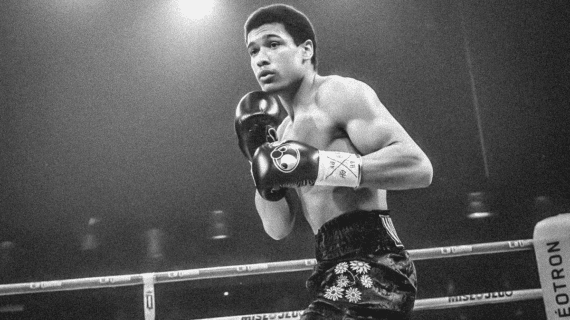

Photo: Vincent Ethier – Darnell Boone

Why do journeymen exist?

Journeymen don’t build undefeated careers. They help build future stars, by offering a credible, realistic opponent who forces them to improve or make adjustments. Thanks to them, many local boxers learn how to take punches, find their rhythm, manage their breathing, and control the ring. Only then are they ready for real fights against gatekeepers, or for prestigious title bouts.

In Quebec, boxers like Stéphane “Brutus” Tessier, Martin Desjardins, or the late Sébastien Hamel have helped train talents like Alexander Povetkin, Oscar Rivas, Jean Pascal, Chad Dawson, Peter Quillin, and many Canadian prospects in need of serious rounds. The fights they’ve delivered — even on hostile ground — served to test, refine, and prepare these prospects for the demands of the elite.

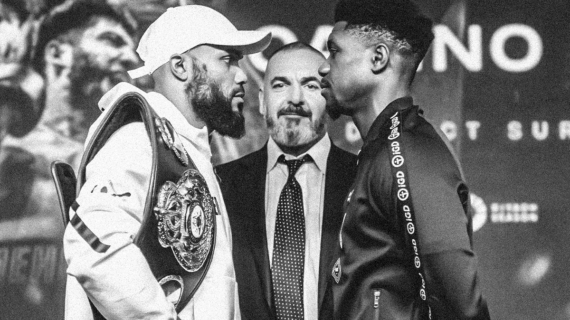

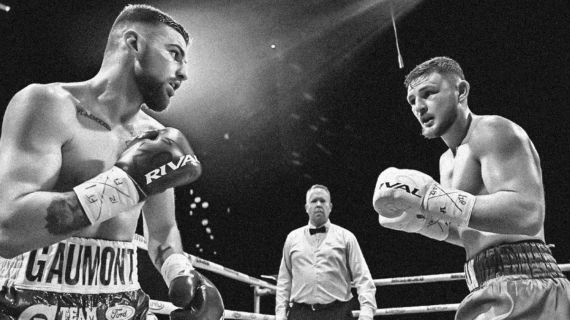

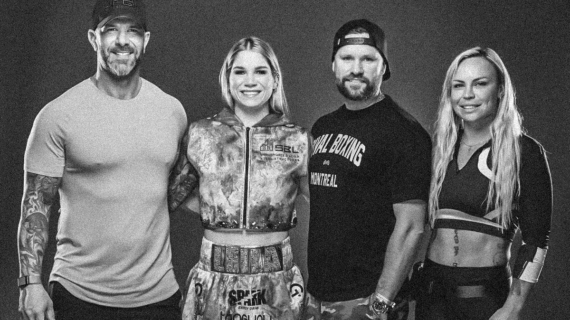

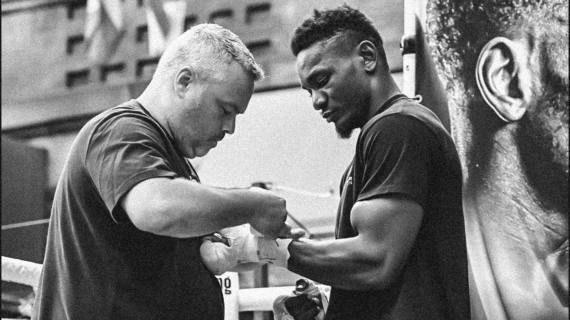

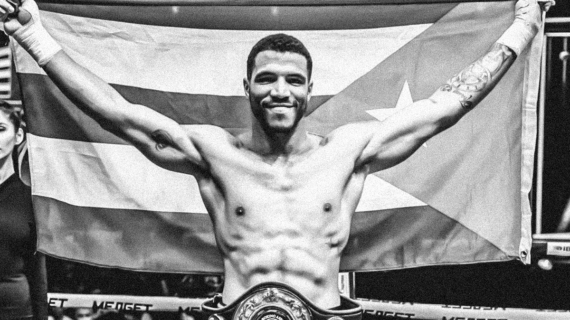

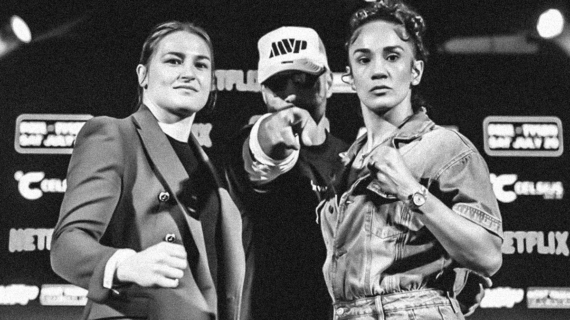

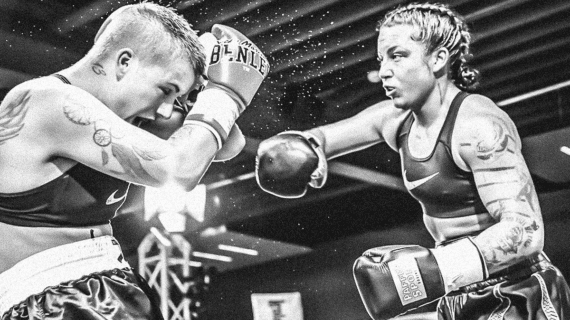

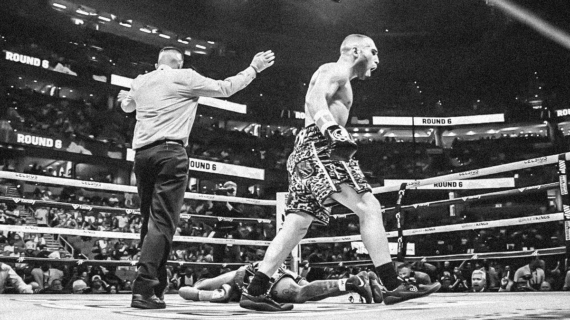

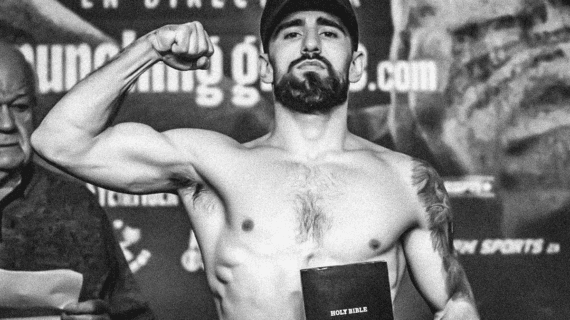

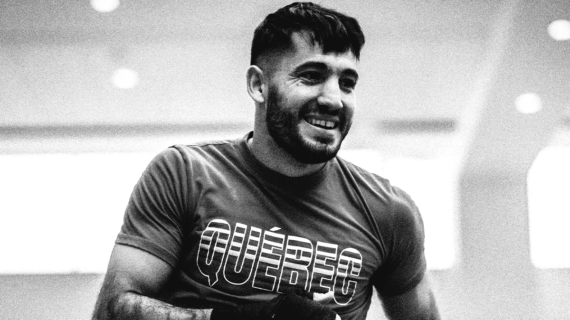

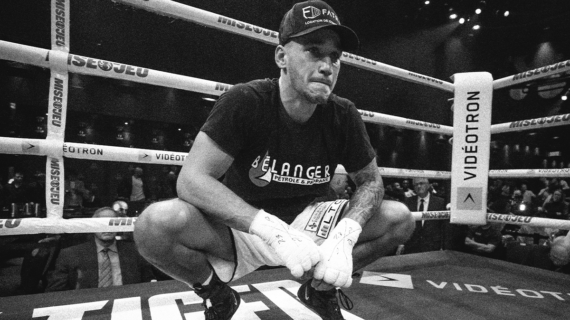

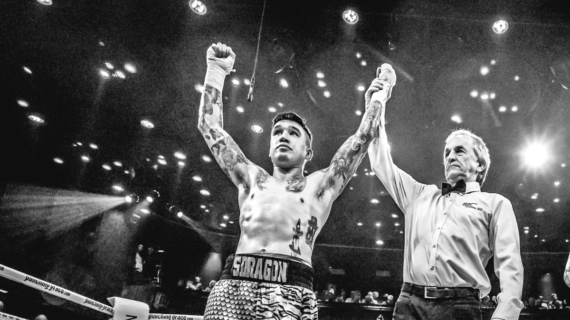

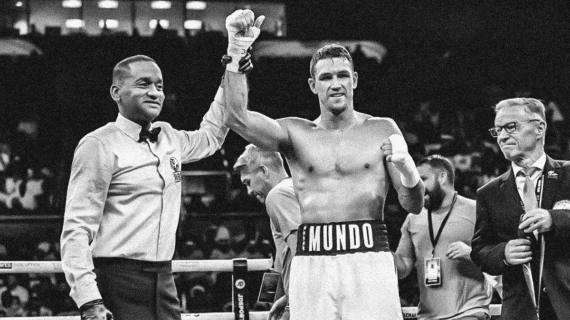

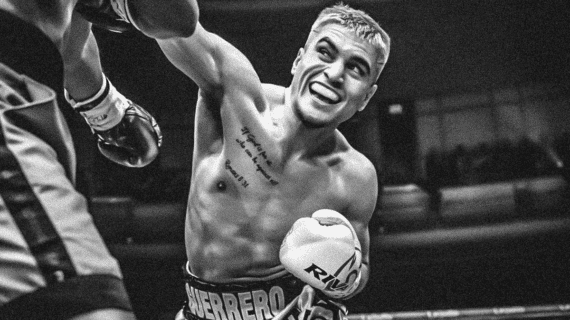

Photo: Vincent Ethier – Facundo Nicolas Galovar

In Quebec, boxing is regulated… but every sport carries risk

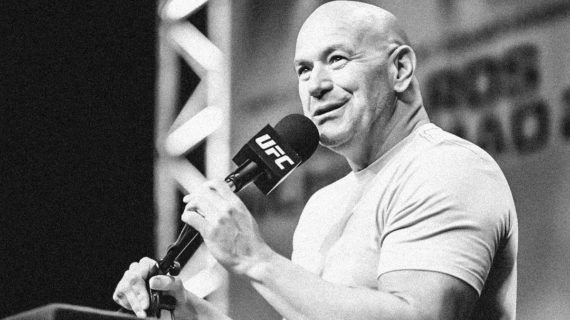

Let’s be clear: no one is forced to step into the ring. Every bout is based on an offer that the boxer is free to accept or decline. Everything is supervised by athletic commissions, with medical exams and appointed officials. But despite this framework, the warrior spirit of fighters often leads them to say yes — even when a fight is ill-advised or premature.

That’s where the responsibility of the trainer — and sometimes the manager — comes in. It’s their job to say no when the challenge is too big or the right conditions aren’t met. It’s their role to protect the athlete. A well-thought-out, well-managed career is built with discernment. Because a boxer will almost always say yes. So we must know how to build for him… sometimes in spite of him.

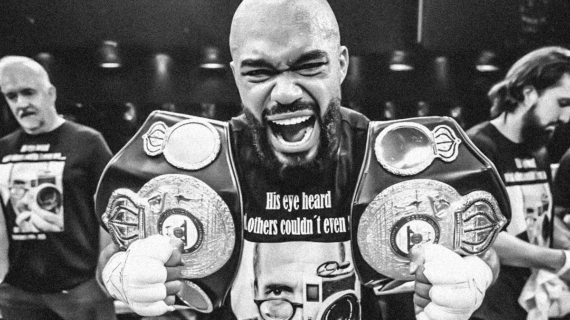

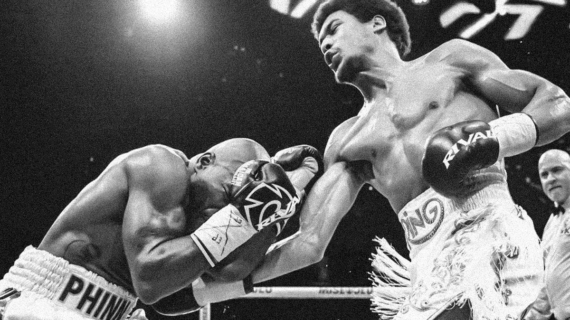

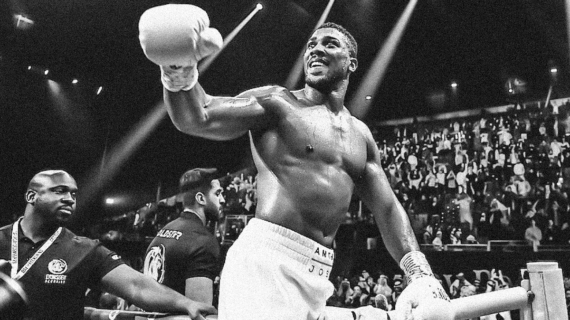

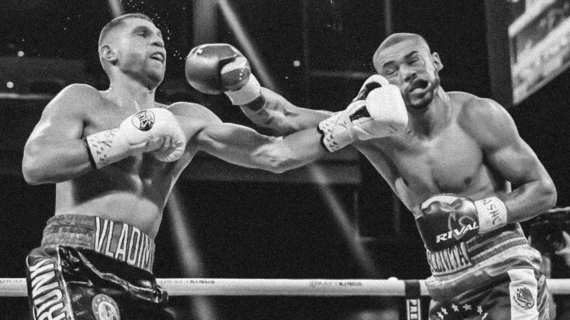

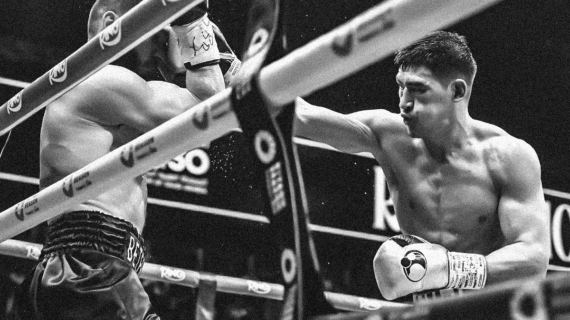

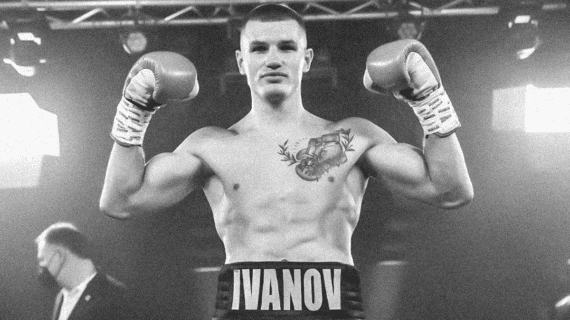

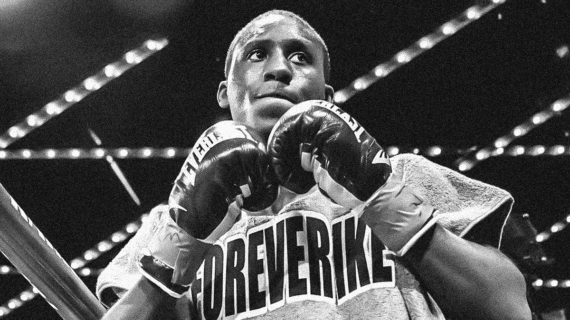

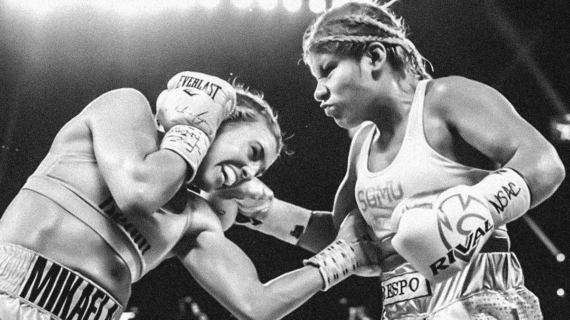

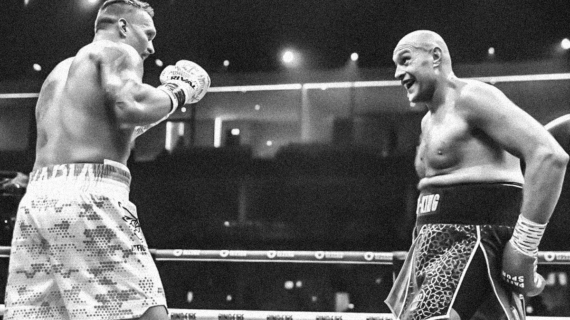

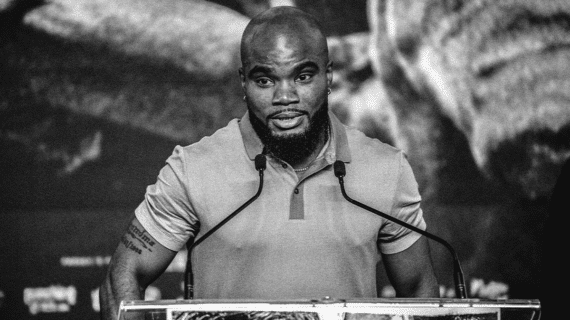

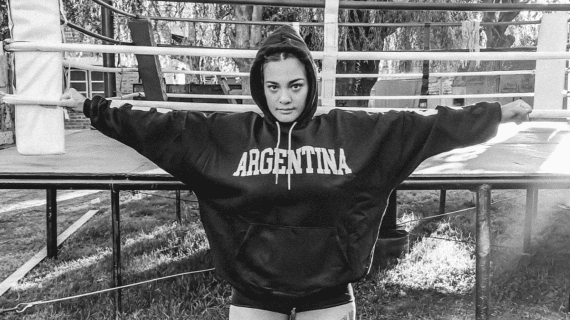

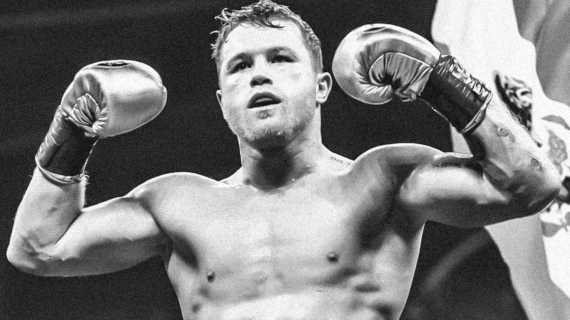

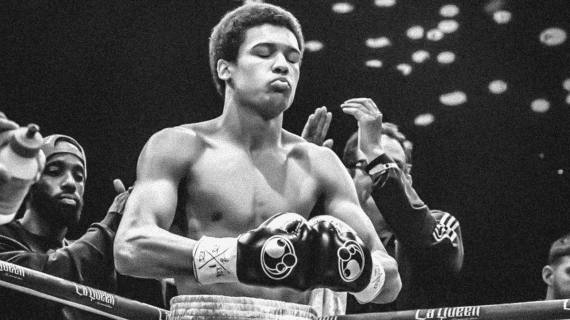

Photo: Vincent Ethier – Ricardo Adrian Luna

Boxing is full of nuance

The journeyman is a pillar. He doesn’t seek the spotlight. He doesn’t seek titles. And yet, without him, there would be no strong next generation, no talented youth rising to the occasion. He is a craftsman in the shadows. Sometimes, he’s the last step before the truth. And he deserves our respect.

He deserves our gratitude.